5 Quick Questions for … Economist Anton Korinek on AI and the End of the Age of (Human) Labor

August 09, 2022

By James Pethokoukis

The machines have never taken all the jobs. There’s always been lots more for humans to do — and lots more that only humans could do. But past results don’t guarantee future outperformance by carbon-based lifeforms. And even though being too early is kinda the same as being wrong, maybe the automation alarmists will eventually be right. In the June NBER working paper “Preparing for the (Non-Existent?) Future of Work,” economist Anton Korinek and researcher Megan Juelfs, both of the University of Virginia, note “concerns that advances in artificial intelligence and related technologies may substitute for a growing fraction of workers, presenting significant challenges for the future of work.” (I’ve previously written about the paper.)

It’s a thought-provoking study that gets around to recommending a universal basic income to redistribute the gains of a robot takeover while acknowledging that work is about more than a paycheck. To take a deeper dive, I reached out to Korinek to get more of his thoughts on AI and the future of work with 5 Quick Questions — and then five more! No extra charge to you, dear subscribers!

Anton Korinek is a professor in the Department of Economics and at the Darden School of Business at the University of Virginia. He is also a David M. Rubenstein Fellow at the Brookings Institution.

1/ The optimistic take on artificial intelligence is that AI will create more high-skill, high-paying jobs. But most Americans don’t have a college degree. What can we do for them, besides a universal basic income?

Let me take this in two parts. First, it was true in the past few decades that technological advances created more high-skill, high-paying jobs and benefited people with college degrees. But it’s yet to be determined if this will also be true in the future. Some are concerned that the most recent advances in AI may actually go primarily after what used to be called high-skilled jobs. If this happens, then all American workers will be pushed into lower-skilled jobs, and whether you have a college degree or not won’t really matter.

Second, if automation does reduce the job opportunities and wages of large parts of the population, we need to think about big solutions if we want to avoid big social turmoil. A universal basic income is not the only big solution — we can also think of broadly distributed capital ownership, etc.

2/ Do you think we’ll ever live in a post-work society? If so, is that an inherently utopian or dystopian society, or something else?

Yes, I do believe that it’s just a question of time. I hope that it will be during my lifetime (I’m 44 …) Depending on how we organize our society, it could be either dystopian or utopian. Much of it depends on whether we find a way to distribute income to those who no longer have work. I am by nature an optimist, so I hope our society will rise to the challenge.

3/ AI and robots that could replace human labor would unleash incredible economic growth, but aren’t there psychological and moral costs to work becoming unnecessary for survival?

Many of us have been conditioned to think of our work as one of the ultimate sources of meaning, but I believe that this is largely a social construct that arose from the necessity of work for survival. When the Industrial Revolution took off, some predicted that there will be huge psychological and moral costs if the majority of people no longer grow their own food. At present only two percent of the population work in farming, but we believe that we are better off. There will be some people who are so set in their ways that the transition will be difficult for them, but I believe that the majority, and in particular the younger generations, will adapt well to the new environment — as long as we ensure that their material needs are taken care of.

4/ Doesn’t the principle of comparative advantage indicate that machines will never be able to replace human labor in much the same way that high-productivity countries still gain from trading with low-productivity countries?

The theory of comparative advantage tells us that there can be mutually advantageous exchange between economic agents that value each other’s products — but it does not predict that the terms of that exchange will be sufficiently favorable for the agents to make a living from it. When AI is sufficiently advanced to perform all human work, humans can still work — but wages may fall so far that they could not make a living from their work or (assuming we find an alternative system of income distribution) that it is no longer worthwhile for them to work.

5/ You’ve predicted that AI will be able to perform any creative or intelligent task at human level in about half a century. What will that transition look like and how should we prepare?

I am leaving such predictions to people who are greater experts on this than I am, and yes, they are indeed predicting this for the second half of this century. I personally think that the transition will be gradual. In fact, we are already living in a world in which we are interacting with AI systems that exhibit superhuman levels of intelligence in narrow domains. These systems will become more and more powerful and ever more general — and I think it is prudent and reasonable to prepare for the possibility that human labor will largely be replaced by the second half of the 21st century — to prepare both at a personal level and for our systems of governance.

6/ You write that “The planner would find it optimal to implement policies that actively encourage work only if work gives rise to positive externalities such as social connections or political stability, or if individuals undervalue the benefits of work because of internalities.” And “systems of taxation will have to adapt significantly if the role of labor in the economy declines. Taxes would have to be raised increasingly on factors other than labor, for example via Pigouvian taxes on activities that generate externalities.” Is AI paving the way to a social engineering nanny state or is that fear unfounded?

When our environment changes, our society needs to adapt, and some of these adaptations will have to involve governmental institutions. For example, when we invented cars, we needed to establish traffic rules. Can you imagine what medieval people would think about all the rules that we have to obey on the road nowadays?!

In the future, if people can’t survive based on work, then it would be cruel to let them starve — we’ll need some societal mechanism to provide for them, and this will indeed have to involve taxation. But that shouldn’t be used as an excuse to curtail people’s liberties more generally — instead, I believe that it could actually enhance liberty by freeing people from the drudgery of work.

7/ You’ve written about the social alignment problem for AI systems. How can we ensure that AI won’t be used to benefit its operators to the detriment of everyone else?

This is an age-old problem — every new technology creates new externalities, and our society has to find new forms of governance to deal with them. In the context of AI, we are just in the beginning stages of figuring out how to solve this governance problem, and right now, we have way too many AI systems that are used by their creators or operators but infringe upon the general interest, as we have learned e.g. from the “Facebook Files.” The difficulty is that AI systems generate a multitude of externalities so we’ll also need a multitude of new governance approaches.

8/ Are there rules or norms we should be adopting now to guide future AI developments?

First, the rules and norms that humanity has developed throughout our history are also relevant for AI — developers have a responsibility to follow these norms rather than “moving fast and breaking things.” As AI is deployed across more and more domains, this is increasingly relevant. Second, yes, we also need to develop a new set of norms that cover the novel capabilities of AI systems for which we have not yet developed norms, e.g., the capabilities of the recommendation models behind social media to manipulate users and society.

9/ As algorithms become more complex and more independent, should we worry about a decline in human agency?

Yes, I am very worried about a decline in our agency and our liberty. I believe that this is a really important concern that both AI developers and policymakers and regulators working on AI governance should look out for.

10/ How will these developments in AI affect developing countries in the Global South?

The Global South is more vulnerable to the displacement of labor than advanced countries because it has a comparative advantage in labor. If labor is displaced, their terms of trade would deteriorate, making them even poorer compared to advanced countries than they already are, and making it very difficult to compensate workers for their last income. I hope that policymakers, technologists, and philanthropists in advanced countries will find a way to share the economic gains that humanity will derive from advanced AI with the citizens of developing countries. (For anybody who is interested in more, [I have a] free online course on “The Economics of AI” at Coursera.)

Bonus: From I, Robot and Blade Runner to The Matrix and The Terminator, many films have depicted a future in which intelligent machines and humans interact. Is there a book, movie, or TV show that does this in a particularly thoughtful way?

All the films you mention present great takes on particular aspects of the challenges and opportunities that we may face in the future. Another one that I like and that has a great take on the so-called AI control problem — on the challenge of how to make sure that we humans can control AI systems that will one day be more intelligent than us — is Ex Machina.

Micro Reads

▶ Baidu to operate fully driverless robotaxis in China – Primrose Riordan and Gloria Li, Financial Times | Baidu has secured a permit to operate China’s first-ever fully driverless licensed robotaxis, winning an early lead in the race to launch autonomous cars in the country. The internet group said on Monday it would be able to operate its Apollo Go cars without a safety supervisor on board in the Chinese cities of Wuhan and Chongqing. … “My best guess is that commercialisation generating significant revenue is still two to three years away,” he said. “Tech-wise, the leaders are Pony.ai and [Baidu’s] Apollo, but in terms of scale and on-ground testing, deployment Baidu is ahead.” The service will be available in the central city of Wuhan from 9am to 5pm, and the south-western Chongqing municipality from 9.30am to 4.30pm, with five robotaxis deployed in each city, said the company. The designated areas of service will cover 13 sq km in Wuhan and 30 sq km in Chongqing.

▶ The Dramatic Failure of Buckminster Fuller’s “Car of the Future” – Alec Nevala-Lee, Slate | On July 21, 1933, the architectural designer and inventor Buckminster Fuller unveiled the first prototype of his iconic Dymaxion Car. It was a streamlined, futuristic vehicle with three wheels, a periscope, and an ovoid body that reminded observers of a tadpole or a flying fish. Fuller—who became famous years later as the visionary behind the geodesic dome—hoped that it would revolutionize both transportation and urban design, but only three were ever made. Today, it endures in the form of a single surviving car, a small number of replicas, and a handful of evocative images captured in photographs and newsreels.

▶ The Case for Longtermism – William MacAskill, NYT Opinion | If we are careful and farsighted, we have the power to help build a better future for our great-grandchildren, and their great-grandchildren in turn — down through hundreds of generations. But positive change is not inevitable. It’s the result of long, hard work by thinkers and activists. No outside force will prevent civilization from stumbling into dystopia or oblivion. It’s on us. Does longtermism imply that we must sacrifice the present on the altar of posterity? No. Just as caring more about our children doesn’t mean ignoring the interests of strangers, caring more about our contemporaries doesn’t mean ignoring the interests of our descendants.

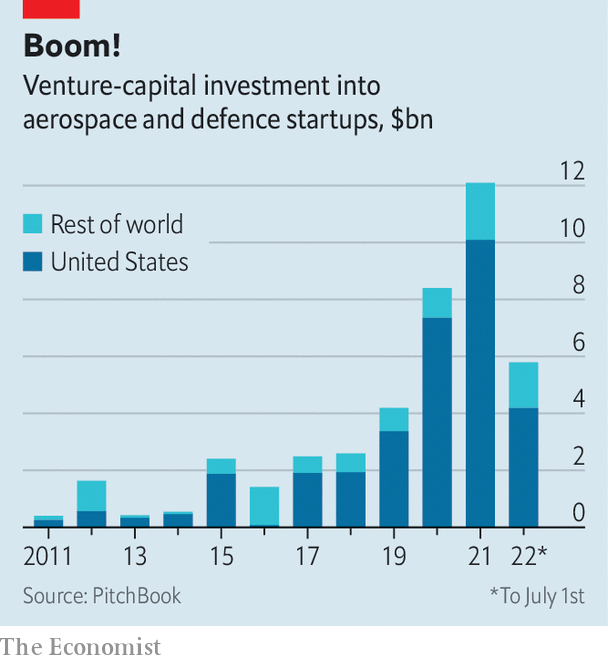

▶ Can tech reshape the Pentagon? – The Economist | Giants from Amazon to Microsoft are pitching for Pentagon contracts. vc funding for American aerospace and defence startups has tripled since 2019, to $10bn (see chart). In the first half of 2022 such firms raised $4bn, down a bit from the last six months of 2021 but not as sharply as for startups overall. On August 8th Palantir, a listed data-analytics firm which works with military and intelligence agencies, reported better-than-expected second-quarter revenues of $473m, up by 26% year on year. The period of estrangement between the crucible of America’s tech and the Pentagon may, in other words, be coming to an end. The renewed bonhomie may reshape America’s mighty military-industrial complex.

Sign up for the Ledger

Weekly analysis from AEI’s Economic Policy Studies scholars