America can grow Faster than China. Let’s make it Happen!

October 24, 2022

In This Issue

The Long Essay: America can grow faster than China. Let’s make it happen!

5QQ: 5 Quick Questions for … economist Adam Ozimek on the geography of remote work

Micro Reads: state capacity, cryonics, self-driving vehicles

Quote of the Issue

“Nations stumble upon establishments, which are indeed the result of human action, but not the execution of any human design.”- Adam Ferguson, An Essay on the History of Civil Science

The Essay

America can grow faster than China. Let’s make it happen!

Item: President Xi Jinping said in his report to the Communist Party congress on Sunday that per-capita gross domestic product will take a “new, giant leap” to reach the level of a medium-developed country by 2035. His renewed pledge implies a doubling in the size of the economy from 2020 levels, a challenging goal given the nation’s slower growth path. That would require an annual average GDP growth rate of around 4.7% in the period, which would be difficult to achieve, economists said. – “China’s Economy Needs to Double in Size to Meet Xi’s Ambitious Plans” (Bloomberg, 10/17/2022)

Item: Chinese markets tumbled on Monday after Beijing rolled out a party leadership packed with Xi Jinping loyalists, and the government said China’s economy expanded by 3.9% in the third quarter of 2022. While above economists’ forecasts, that left growth for the first nine months of the year at 3.0%, putting China on pace to miss its official full-year target of 5.5% by a large margin. … Excluding 2020, this year is almost certain to be the country’s slowest year of growth in a generation. … Many economists believe Xi will [give] priority to political objectives—including bigger roles for inefficient state-owned enterprises in the economy and a continued emphasis on strict Covid-control measures—instead of more pragmatic steps to ensure a strong recovery. – “China’s Xi Jinping, Secure in Power, Faces Deepening Economic Challenges” (WSJ, 10/24/2022)

I’ve long argued that a key long-term benchmark for successful US economic policy should GDP growth that’s as fast in the future as in the past — or, more specifically, the post-World War II era. To be even more specific: real GDP growth in excess of 3 percent annually. That’s no easy task given the size of the American economy and its changed nature over the decades. Slower post-baby boom workforce growth means faster productivity growth is needed to hit that 3 percent target. Then again, the whole point of this newsletter is to argue that better public policy combined with a Big Wave of discovery/invention/innovation makes hitting or exceeding that goal a realistic possibility. You know, faster, please!

Now let me add an additional goal that I think is both worthwhile and possible: Growing faster than China over the course of the 21st century.

You might recall that presidential candidate Donald Trump made a similar suggestion back in 2016, to much ridicule. This is what Trump said back during his final debate with Hillary Clinton as reported by The Washington Post:

“They’re growing at 8 percent,” Trump said of India. “China is growing at 7 percent. And that for them is a catastrophically low number. We are growing — our last report came out — and it’s right around the 1 percent level. And I think it’s going down. … Look, our country is stagnant.” Later, Trump pledged that his economic plan would restore America’s growth to much higher levels: “But we’re bringing it from 1 percent up to 4 percent. And I actually think we can go higher than 4 percent. I think you can go to 5 percent or 6 percent. And if we do, you don’t have to bother asking your question, because we have a tremendous machine. We will have created a tremendous economic machine once again.”

There’s nothing wrong with comparing your country’s economic performance to that of others, especially geopolitical rivals. In the early 1960s, for instance, Washington was gripped by worry that other economies were outperforming America’s. President John F. Kennedy, in particular, was alarmed that the German, Japanese, and even Soviet Russian economies had outgrown America’s during the 1950s. But such concerns were silly. Those economies were all playing catch-up after wartime devastation, while Soviet Russia was also much poorer than America.

Likewise regarding Trump’s comments, Washington Post reporter Ana Swanson correctly explained in her piece back then that comparatively rapid growth by China and India stemmed from those countries being at different stages of development. China and India are still much poorer than America on a per-person basis, but they are also absorbing outside investment and technology to catch up to the US and other rich economies.

Much of the commentary back then also argued that it would be ridiculous to expect an advanced economy to grow at such rapid rates given demographics and the difficulty of generating fast productivity growth. Indeed the US hasn’t posted consecutive years of 6 percent growth since the 1960s, percent growth since the 1970s, 4 percent growth since the 1990s, or 3 percent since the early 2000s. So matching China’s projected growth rate, 4.7 percent annually as mentioned above, should hardly be anyone’s baseline forecast.

China, welcome to your new normal

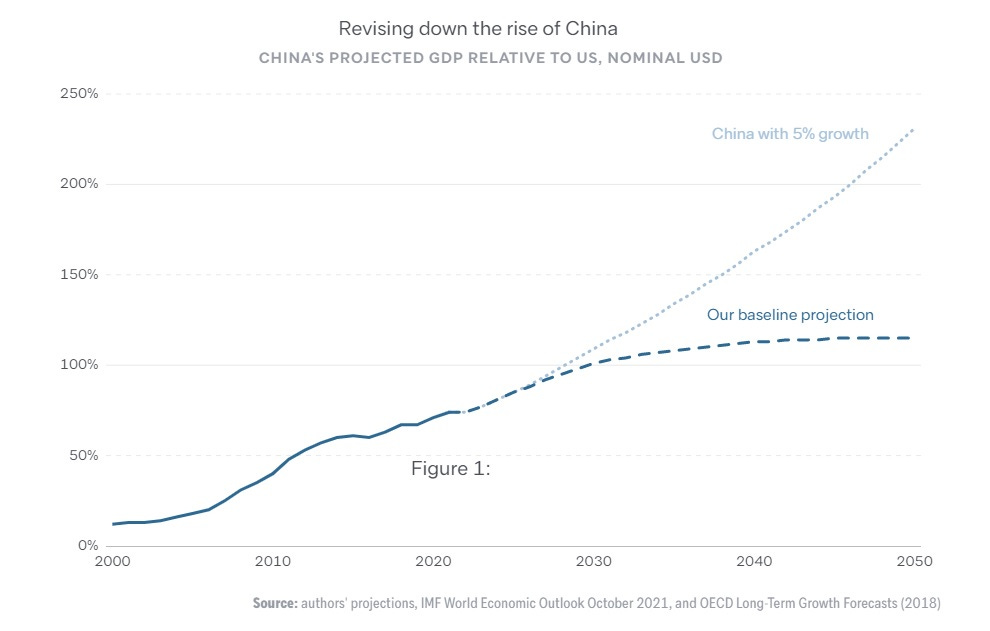

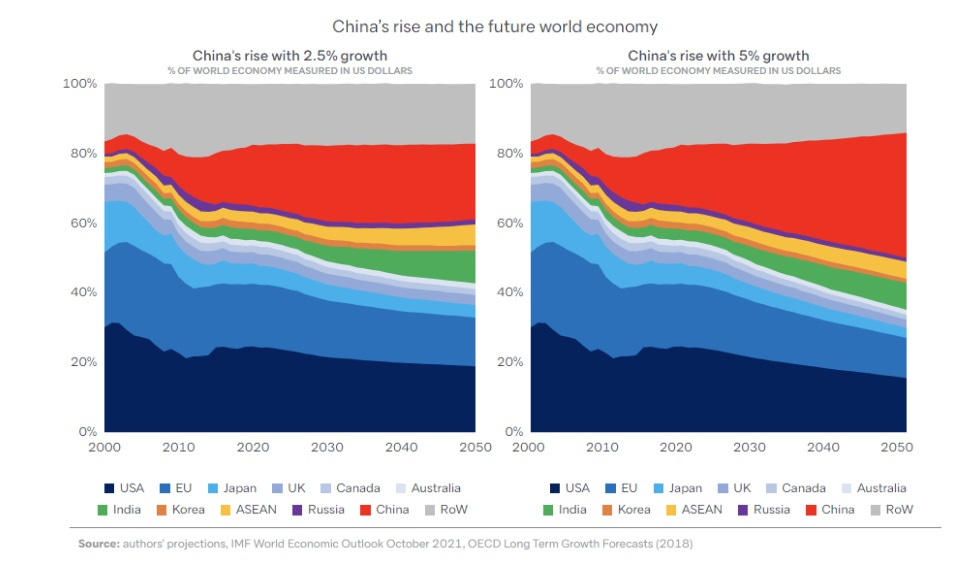

But what if China is only a 3 percent economy going forward? Hey, what’s a couple of percentage points between global competitors? Well, quite a bit. If China were to continue to grow at a 4 percent or 5 percent rate, it would make China the world’s undisputed economic and likely technological superpower by mid-century — with all the military implications such leadership suggests. But if China only grows around 2 percent to 3 percent a year, then the country’s future looks very different. “China would still likely become the world’s largest economy,” concludes a recent report from Australia’s Lowy Institute. “But it would never establish a meaningful lead over the United States and would remain far less prosperous and productive per person than America, even by mid-century.” As the two charts below show, we are talking about a different country and different global balance of power:

And what is the 3 percent growth case for China? This from the Rhodium Group:

The code of silence among most sell-side institutions and global policymakers regarding the quality of China’s GDP data has consistently created false assumptions about China’s growth and the potential for policy mistakes in response to mistaken economic signals. The costs of refusing to engage with economic reality are rising because even onshore market analysts are reluctant to publish any bad news or negative forecasts. … Over a longer horizon, China’s growth outlook is constrained by demographics, falling productivity, and more significantly, the failed structural reforms of the past decade. …China’s potential growth rate at present is probably closer to 3% than 5%, and China is currently growing well below that potential rate. With the property market and the financial system in distress, it may take several years to close that output gap, even if policy is more supportive. Yet the current consensus expectations for GDP growth are 5.2% in 2023 and 5.1% in 2024.

And this from BlackRock economists Alex Brazier and Serena Jiang:

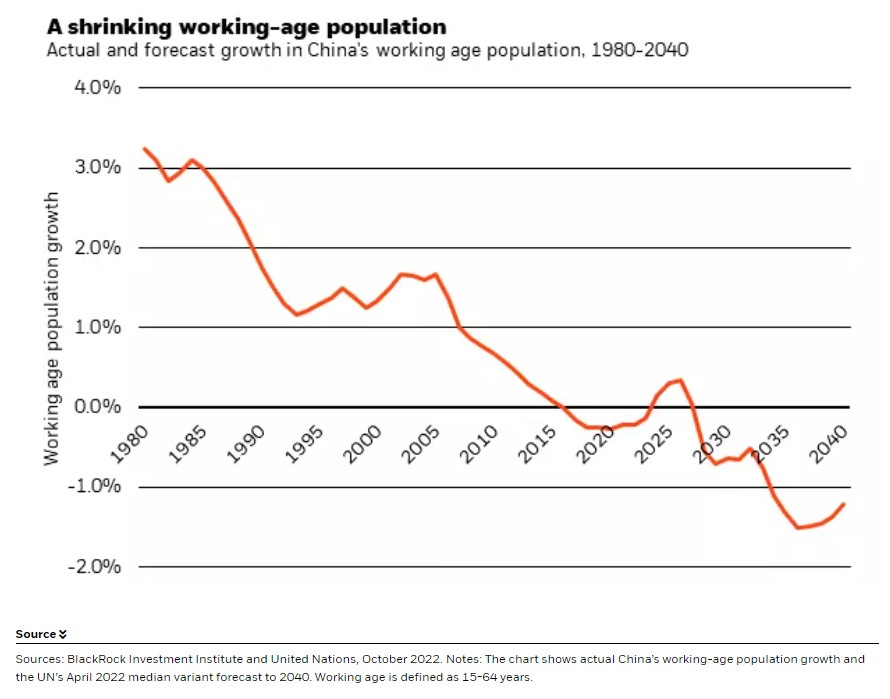

Covid controls are reducing potential output today. While they might be eased, we still think the potential growth rate of the Chinese economy might have fallen below 5% and could fall further to around 3% by the turn of the decade. Why? Most importantly, the working age population, having grown rapidly, is now shrinking. … Fewer workers mean the economy cannot produce as much without generating inflation, unless productivity growth accelerates. But we think international trade and tech restrictions, as well as tighter regulations on companies operating in China, will dampen productivity growth.

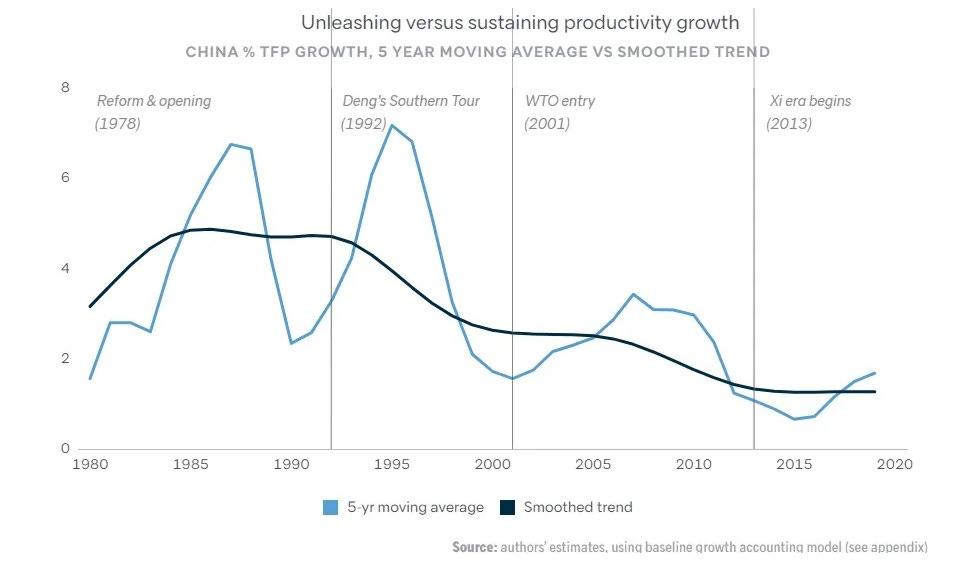

China’s productivity problem

This leaves higher worker productivity as the key to fast economic growth going forward. And even before efforts by the Biden administration to kneecap the Chinese technology depriving it of the advanced chips, Chinese productivity growth was slowing or even turned negative. This should not be surprising given China’s retreat from economic liberalization as seen in President Xi Jinping’s “common prosperity” program, actions meant to accelerate China’s shift away from Western-style market capitalism and economic openness.

For example: As the World Bank noted in 2020, “Earlier reforms led to state-owned enterprises catching up to private sector productivity levels in manufacturing, but convergence stalled after 2007.” And this from the Harvard Business Review in 2019: “All companies with more than 50 employees must have a Communist Party representative on-site. This muddies decision making, skews rewards, and bureaucratizes the innovation process.”

So what about the other question here: Can the US grow at least three percent going forward? Certainly that’s not the baseline forecast of most economists, including those who work at the Congressional Budget Office or the Federal Reserve. But I think it can. There’s nothing wrong with the American economy that cannot be fixed with what’s always been right with the American economy. That means an economy that welcomes and attracts global talent, spends massively on R&D (both public and private), regulates with a consideration to how new rules affect the ability to build and innovate in the physical world, and continues to reward high-impact entrepreneurship. No one policy is a silver bullet, but rather looking at all policies through a growth lens and making sure it all adds up to a holistic, pro-growth economic ecology.

The immigration piece is obviously superimportant here and something China cannot match. From the WaPo:

By some estimates, the United States needs at least 50,000 new semiconductor engineers over the next five years to staff all of the new factories and research labs that companies have said they plan to build with subsidies from the Chips and Science Act, a number far exceeding current graduation rates nationwide, according to Purdue. Additionally, legions of engineers in other specialties will be needed to deliver on other White House priorities, including the retooling of auto manufacturing for electric vehicles and the production of technology aimed at reducing U.S. dependence on fossil fuels.

So let’s get to it, America!

5QQ

5 Quick Questions for … economist Adam Ozimek on remote work

Adam Ozimek is chief economist at the Economic Innovation Group. Earlier this year, he and Eric Carlson published “The Uneven Geography of Remote Work.” It’s an important report because remote work has the potential to shake up the geographic distribution of talent and opportunities in the US, perhaps giving “left-behind” localities — or maybe cities with more affordable housing — the ability to benefit from the productivity of superstar metros like Boston, San Francisco, and New York. From that analysis:

Remote work has increased drastically compared to before the pandemic, that much is clear. This rise in telework offers new opportunities for the economic development of communities across the country by loosening the grip that superstar cities have on skilled knowledge workers. … [W]ithin the United States there has been significant variation in the extent to which populations have benefitted from remote work. Importantly, while remote work is concentrated along the coasts, we do see that there are places in every region and places outside of superstar cities with high levels of remote work. It should not be considered entirely a coast or superstar city phenomenon.

Below, you’ll find Adam’s answers to 5 Quick Questions I asked him about the report.

For more on this topic, you might consider checking out two recent podcast chats I’ve done with Stanford economist Nick Bloom and Brookings Institution senior fellow Mark Muro.

1/ What should non-superstar localities be doing to attract remote workers?

We should think about this question in the context of competition between places. Before remote work, some places had a major advantage stemming from their labor markets. Some places had a major competitive advantage because people wanted to live there to have access to the labor markets. In contrast, other places were at a competitive disadvantage because of lack of good jobs.

This represents an increase in competition and also a change in the nature of competition. Competition is changed because remote work helps to level the playing field between places. Places that could formerly count on their strong labor market to outweigh affordability and quality of life problems are less able to do so today. It also means places can compete directly for people instead of being focused on luring in employers.

In practice what this means is that places without significant labor market agglomeration will be more able to compete for residents of superstar cities on affordability and quality of life basis. These places should spend less effort on luring in big businesses with tax incentives and more effort on deregulating housing, providing efficient and quality government services, encouraging good amenities, and addressing quality of life issues. Post remote work, on the margin, places should compete for people more and businesses less.

2/ How much of the spike in remote work do you expect is permanent? Should we expect a significant number of workers to re-enter the in-person workforce this year?

We don’t measure remote work very well in real-time right now, so it’s a little hard to say exactly how many are working remotely right now. The Bureau of Labor Statistics will be fixing this soon with some good remote work questions being added to the Current Population Survey, but in the meantime if you look at Kastle systems data, it seems like there has been a plateau for office workers back to the office each day. I don’t think there is much more back-to-the-office to come.

In fact, I think long-run competition, technology, and the desires of workers will be pushing more businesses to go remote. Some businesses who are recalling workers back to the office are correctly judging that the costs and benefits dictate that their work be done in person. We are in no way going to be a 100 percent or even majority remote economy. However in some cases, that decision will prove incorrect. Businesses are no doubt using their best judgment, but in some cases that judgment is being affected by the baggage of long-standing organizational processes, as well as the false beliefs and costly preferences of current management and ownership. I believe that we will see startups learn to adapt remote work in places where incumbents’ baggage proves to be a blocker. At the end of the day, it mostly doesn’t matter what managers and owners want. Competition is the ultimate arbiter.

3/ The geography of remote work is interesting, but why is it worth studying? Why does this matter?

I believe that the geography of remote work helps to inform the impacts that it will have on the economic geography of the US. Over the last few decades, economic activity has been increasingly clustered in superstar cities in large part due to agglomeration effects. There are a few negative results of this trend, including large parts of the country experiencing outright population loss and especially the loss of the most educated people. In addition, those superstar cities have failed to build enough housing, leading to skyrocketing cost of living. I believe remote work has the ability to lean against those trends and help spread economic activity throughout the country. To understand if that is starting to happen, we need to understand the geography of remote work.

4/ You call for more research into how housing costs affect telework. How do you think housing costs and remote work interact? What are the most important open questions?

We see evidence that remote work is allowing people to move away from the most expensive places towards less expensive places. This is occurring within metros, as people move from the expensive core to lower-cost exurbs and suburbs. This is the so-called donut effect, coined by Nick Bloom and Arjun Ramani. It is also occurring between metros, as people move out of high-cost metros altogether and into lower-cost ones.

The housing market right now is a bit chaotic, and is currently under pressure from high demand and lack of new construction. But longer run, the ability to engage in more geographic arbitrage and move towards places that actually build housing should help lower cost of living and increase real incomes. It’s important we continue to focus on making inelastic housing markets more elastic, but in the meantime it’s helpful that remote work gives people more ability to move towards more elastic places as well.

5/ Is it a good sign that a commuting zone has a high telework share? Should localities be trying to encourage more remote work, or is that against the interests of the local economy?

Having lots of remote work is both an opportunity and a threat. It can be an indicator that you are a good place for remote workers to live, and therefore in the long run will gain a growing population of remote workers and enjoy the spillover benefits that creates. On the other hand, it comes with the risk that the existing population will enjoy the newfound mobility that remote work brings and move away. I would say remote work is closest to being a threat when it is accompanied by high housing costs not backed up by a commensurate level of amenities. Remote work gives people the ability to leave, high housing costs give them a reason to.

Micro Reads

▶ US Daily: How We Think About Recession Risk (Mericle) – Goldman Sachs Economics | The US economy does not appear to be on the brink of recession at the moment. … Our recession odds of 35% over the next 12 months are roughly triple the unconditional average for a typical year in recent decades but are well below the 63% consensus odds. One aspect of the consensus forecast that we are particularly skeptical of is the implicit view that rate hikes of the size we expect or just a bit larger will be enough to cause a recession.

▶ Incapacitated: How a lack of state capacity doomed pandemic results – Brink Lindsey, Niskanen Center | My conclusion, then, is that governance failures – the inability of American public health authorities to do the job that they were widely considered to be the best in the world at doing – are the primary reason for the country’s poor record in dealing with the pandemic. The overwhelming majority of the nearly 350,000 fatalities during 2020 (i.e., before vaccines) could have been avoided, and that accomplishment could have saved many of the 300,000-plus avoidable deaths caused by vaccine resistance.

▶ Why the sci-fi dream of cryonics never died – Laurie Clark, MIT Tech Review | Since its beginnings in the late 1960s, the field has attracted opprobrium from the scientific community, particularly its more respectable cousin cryobiology—the study of how freezing and low temperatures affect living organisms and biological materials. The Society for Cryobiology even banned its members from involvement in cryonics in the 1980s, with a former society president lambasting the field as closer to “fraud than either faith or science.” In recent years, though, it has grabbed the attention of the libertarian techno-optimist crowd, mostly tech moguls dreaming of their own immortality. And a number of new startups are expanding the playing field

▶ The driverless car revolution is stuck in the slow lane – Elaine Moore, FT Opinion | Still, the money keeps coming. Either driverless cars are an example of sunk cost fallacy or their slow start is not seen as a hindrance to eventual adoption. Uber has signed a deal with Motional — the start-up that works with Lyft to offer autonomous vehicle rides in Vegas. Volkswagen’s automotive software subsidiary Cariad is investing $2bn in a partnership with Chinese chipmaker Horizon Robotics. Waymo is planning to expand its robotaxi service to Los Angeles and Cruise hopes to get regulatory approval for robotaxis without pedals or steering wheels. It has been a slow and expensive road. It may still be years before the cars are widespread. But for many of the biggest companies in the world, driverless vehicles are still inevitable.

Sign up for the Ledger

Weekly analysis from AEI’s Economic Policy Studies scholars