Could Supersonic Air Travel Take Flight (Again)?

August 20, 2024

The existence of the NBA’s Oklahoma City Thunder offers an interesting bit of irony, as least to my mind. Originally the Seattle SuperSonics, a name inspired by Boeing’s supersonic transport project a half-century ago, the basketball team’s current moniker still evokes the thunderous sound of breaking the sound barrier.

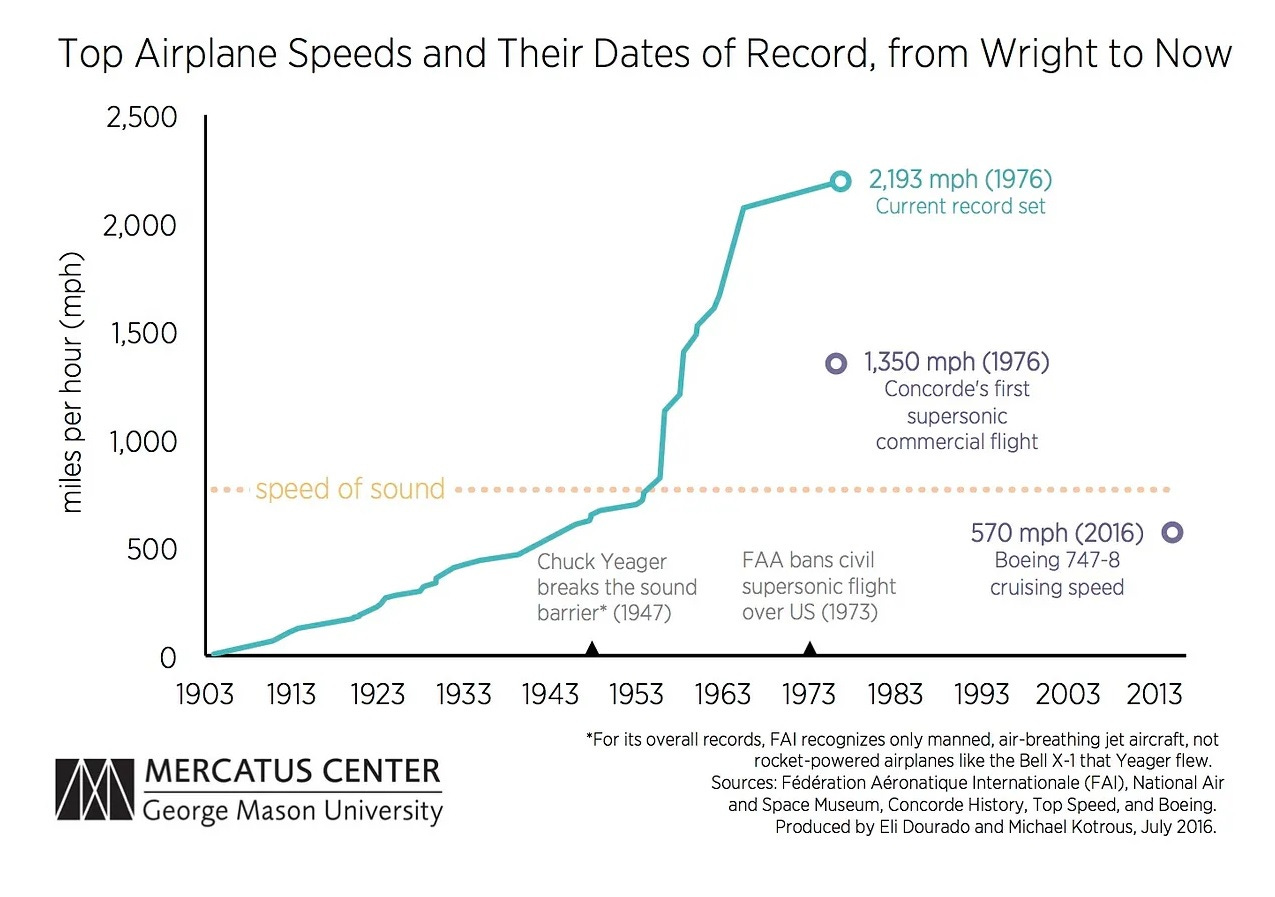

Yet the SuperSonic-Thunder now play in a city with a pivotal role in supersonic flight’s commercial downfall. In 1964, Oklahoma City became the stage for an FAA-commissioned test where residents endured eight sonic booms daily for six months. This test, conducted using fighter jets rather than specially designed quieter airliners, provided anti-SST activists with compelling evidence against overland supersonic flight. The data gathered in Oklahoma City ultimately contributed to the ban on supersonic transport over the continental United States. Thus, a team born in Seattle from the excitement of aerospace innovation now resides in the place that helped clip its wings.

Today, however, aerospace engineers are experimenting with “low-boom” models in the hopes of relaunching an era of supersonic commercial aviation. I asked Jacek Krywko a few quick questions about what it might take to get these designs off the ground. Krywko is an associate writer at Ars Technica, last March writing the piece “After Concorde, a long road back to supersonic air travel.” His areas of interest include space exploration, AI, computer science, and engineering. He previously worked as a staff journalist at Gazeta Wyborcza, a major Polish newspaper.

1/ When, if at all, can we expect supersonic commercial air travel to become available?

The return of commercial supersonic air travel largely depends on changing the regulations that prohibit flying at supersonic speeds over land. NASA currently works with CAEP (Committee on Aviation Environmental Protection) to replace the Mach 1 speed limit with a standard based on noise which would allow planes to supersonically fly over land if they are quiet enough to not be a nuisance. Hopefully, this new standard will be in force by 2031 and, if that happens, we’ll probably see the first commercial supersonic airliners around the mid-2040s.

2/ How would the design of a modern supersonic commercial jet differ from that of the Concorde?

Future supersonic commercial jets will need to be quiet, which means they would need to follow what NASA and Lockheed Martin call a low-boom design, which Concorde didn’t. It’s hard to say how this design will look when implemented in a large jetliner, but Lockheed’s X-59, the latest experimental low-boom supersonic jet, has a very long nose with no traditional windscreen and a very flat, clean underbody with engine inlets located at the top, rather than at the bottom of the plane. I’d expect to see many of the X-59’s features carried over to commercial planes in the future.

3/ What would the economic ramifications be of popularized supersonic air travel?

Supersonic jets need to be long and slender, which limits the number of passengers they can take onboard. They also use way more fuel than subsonic airliners. Concorde used roughly four times more fuel than a Boeing 747 on a Paris-New York flight and could take around 100 passengers, which is one-fifth of the 747’s capacity. Supersonic flight in the future will be available to people who can afford first-class tickets. Sure, the future supersonic jetliners will hopefully be more efficient than Concorde, but this will likely lead to maybe including a business class one day. They will never be more affordable than subsonic jets.

4/ Could the military benefit from a lift of the ban on supersonic air travel over land?

I think that’s unlikely. Military jets are designed for lethality and effectiveness in combat. Noise, while important, is rarely a primary concern. So, I wouldn’t expect military jets to adhere to those new noise-based standards even if these standards come into force one day. Today, the military can supersonically fly over land above 30,000 feet with no limits, and in designated areas when below 30,000 feet. I’d place my bet on this staying that way.

5/ Is there a fuel-efficiency argument against supersonic flight, and are there ways of improving this problem?

Supersonic jets are way less fuel-efficient than subsonic jets. First there is the wing design, which works well at supersonic speeds but gives less lift than a wing in a subsonic airplane. This means the engines need to give more thrust during takeoff and landing, which burns up more fuel. Then, lots of fuel is needed to accelerate to supersonic speed and maintain it.

So far, the idea to improve fuel efficiency is to make future supersonic airliners fly a bit slower than Concorde. Concorde flew at around Mach 2. Future supersonic airliners will likely fly at around Mach 1.6–1.8 which is considered a sweet spot between speed and fuel-efficiency. That’s slower than Concorde but still twice as fast as a subsonic plane. The hope is this would improve fuel consumption.

Sign up for the Ledger

Weekly analysis from AEI’s Economic Policy Studies scholars