Good News: We Know How to Accelerate the US Economy

February 15, 2024

Quote of the Issue

“The fall of Empire, gentlemen, is a massive thing, however, and not easily fought. It is dictated by a rising bureaucracy, a receding initiative, a freezing of caste, a damming of curiosity — a hundred other factors.” – Isaac Asimov, Foundation

The Essay

⏩🔬 Good news: We know how to accelerate the US economy

In The Conservative Futurist: How To Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised, I do my best to explain what caused the Great Downshift, my descriptor for the persistent multi-decade slowdown in economic and productivity growth that began around 1973. It really does rival the Great Depression in importance.

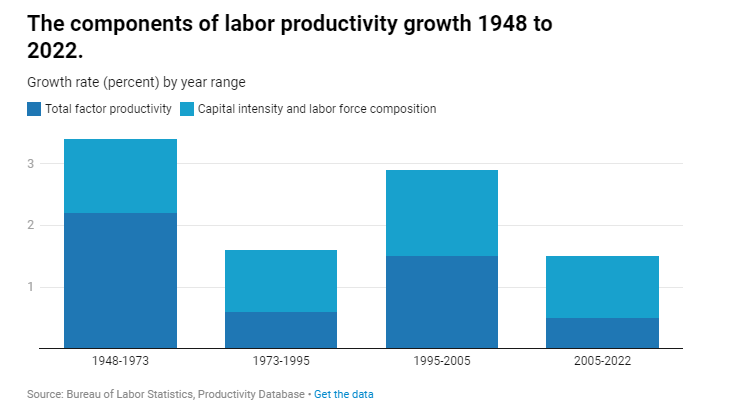

Post-WWII to 1973, US economic growth was powered by a rapid 3 percent annual labor productivity growth rate. This productivity surge came from two sources: 1) improvements in workforce education/training and more physical capital (machinery, buildings, infrastructure) available per worker, and 2) new techniques and technologies, or “total factor” productivity growth. TFP accounted for two-thirds of the strong postwar productivity gains. As I write:

TFP pushes forward the frontier of what an economy can be capable of tomorrow. That’s why I refer to TFP growth as Technologically Futuristic Productivity growth. From 1948 through 1973, TFP accounted for two-thirds of overall productivity growth.[i] TFP is a key piece of the arrow of prosperity: tech progress and innovation (factories shifting to electric motors from steam, jet engines, atomic reactors, the shipping container, the microchip) drive TFP growth → TFP growth drives labor productivity growth → productivity growth drives economic growth → and economic growth drives higher incomes for everyone.

Then came the Great Downshift. Over the next quarter century, TFP grew at just a quarter of the rate that it did during the previous quarter century. And although TFP surged during the 1995–2004 economic boom, it then sank back to its sluggish post-1973 pace right up to the present day.

A key difference between the Great Depression and Great Downshift: The impact of the former was obvious: bankrupt businesses, foreclosed farms, unending unemployment lines. With the latter, however, what we lost was a future of greater prosperity, health, and societal resilience. It’s a story of opportunity cost, the loss of potential gains from other alternatives when a different decision is made.

Indeed, it’s my contention in The Conservative Futurist that our decisions played a key role in the Great Downshift. Sure, there were external macro factors at play, important ones: the destruction of scientific communities during World War II, the 1970s oil shocks, the one-off nature of foundational late 19th century innovations, ideas becoming harder to find as science advances, the end of exponential growth from Moore’s Law in computing, and maybe even COVID-19 disruptions.

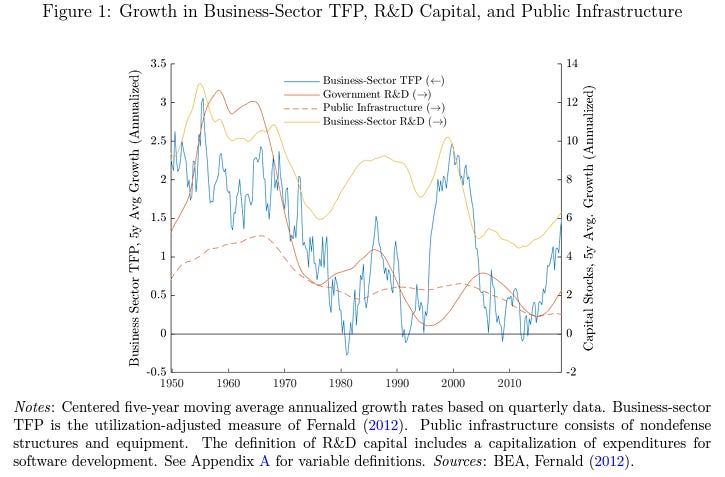

But we shouldn’t let ourselves off the hook. One bad decision relates to this chart:

Again, since the late 1960s, apart from a brief uptick in the late 1990s and early 2000s, US productivity growth has significantly slowed. This downturn neatly aligns with reduced public investments in research and development. But is this just correlation or also causation? That was the question pursued in a Dallas Fed paper from December, “The Returns to Government R&D: Evidence from U.S. Appropriations Shocks.” Economists Andrew J. Fieldhouse and Karel Merten studied historical federal budgets to pinpoint major changes in government research funding approvals, splitting them into defense and nondefense categories. They then tracked how business-sector TFP responded over long stretches, up to 15 years after these research funding shocks.

- Increases in nondefense R&D appropriations lead to statistically significant, gradual increases in aggregate TFP over long horizons of 8–15 years. A one percent increase in nondefense government R&D eventually boosts TFP by around 0.2 percent.

- Nondefense government R&D accounts for approximately one quarter of business sector TFP growth since WWII. This contribution is of similar magnitude, or potentially even larger, than that of public infrastructure investment, despite much lower spending.

- The estimated rates of return on investments in nondefense R&D range from 150 percent to 300 percent.”These estimates are considerably higher than similar ones for the return on public infrastructure. Our findings therefore point to a misallocation of public capital, and substantial underinvestment in non-defense R&D.”

- In contrast to nondefense R&D, the economists find little evidence that positive shocks to defense R&D appropriations cause any significant or persistent future increases in TFP.

- Nondefense R&D appropriation shocks lead to relatively greater increases in spending on more fundamental or basic research, especially research performed at universities. Defense shocks predominantly expand funding for development work and applied research conducted by private businesses.

- Both defense and nondefense R&D shocks stimulate some amount of additional private spending on R&D. However, nondefense shocks also gradually spur the expansion of roads, utilities, and education infrastructure by state and local governments over time.

In a separate and just-published analysis of their findings, Fieldhouse and Mertens write:

U.S. productivity growth has slowed markedly since the late 1960s—apart from the information technology revolution near the start of the century—and government-funded R&D heavily contributed to the faster postwar rates of productivity growth. Our estimates indicate that government-funded R&D accounts for roughly one quarter of all business sector productivity growth since World War II, including one quarter of the deceleration in productivity growth since the late 1960s. Correlation does not imply causation in general, but our new causal evidence lends support to the thesis of Gruber and Johnson about the important relationship between government-funded R&D and U.S. productivity growth.

That bit about “Gruber and Johnson” refers to economists Simon Johnson and Jonathan Gruber who argue in their 2019 book, Jump-Starting America: How Breakthrough Science Can Revive Economic Growth and the American Dream that government-funded R&D is a key driver of productivity growth that America should greatly boost public R&D.

Lucky for me, the paper also lends support to my thesis, as outlined in the book. I point out that the American science and technology innovation system has been likened to a “miracle machine” that promises substantial returns on investment. One paper I cite finds a $1 investment in R&D is estimated to yield $5 in benefits, including improved living standards, health, and worker productivity. This analogy underscores the transformative potential of strategic investment in science and technology. Economist Benjamin F. Jones suggests that doubling R&D spending could boost US productivity and income growth by 0.5 percentage points annually, significantly enhancing living standards and America’s global economic positioning over time.

During the 1960s Space Race, the US allocated nearly three percent of GDP to scientific and technological R&D, with government and business contributions at two percent and one percent, respectively. But now those numbers are flipped, with business contributing two thirds and government a third to that three percent. And that government number will barely change even with legislation such as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act.

Look, I would boost federal R&D spending to levels seen back during the Apollo, as a share of GDP. That’s far from the only pro-productivity idea in the book. Indeed, some other ideas — especially regarding immigration and meta-science — would be supportive of higher public R&D spending, in terms of both efficiency and mimimizing the possibility of crowding out or otherwise negatively affecting corporate R&D. But I think the weight of the evidence does favor increased spending.

Sign up for the Ledger

Weekly analysis from AEI’s Economic Policy Studies scholars