“Hello, I Must Be Going.” Another Look at the Pandemic-Era Productivity Boom—Then Bust.

September 05, 2022

The economic silver lining of the first two pandemic years, 2020 and 2021, was strong US productivity growth. (Econ 101 boilerplate: Almost all variation in living standards among countries is due to differences in productivity, or the amount of goods and services produced from each unit of labor input. Companies can raise wages without fueling inflation if workers become more productive.) Specifically, nonfarm labor productivity averaged over 2 percent annually during those two years, twice the rate of the post-Global Financial Crisis period of 2010 through 2019. Real-time explanations included the rise of e-commerce, companies digitizing their workplace (such as work-from-home), and the “creative destruction” of low productivity businesses going out of business. So despite all the economic pain caused by the pandemic, the outbreak seemed to have left a more efficient economy in its wake.

But maybe not. The first half of 2022 has seen a big reversal from those higher-productivity years, with annualized declines of 7.4 percent in the first quarter and 4.1 percent (upwardly revised by 4.8 percent in the initial print) in the second quarter. “The abysmal productivity readings in the first half of 2022 have cast doubt on whether the pandemic generated efficiency gains in the first place,” observes the Goldman Sachs economics team in a new research note. “At face value, this year’s GDP and employment numbers imply a full reversal of the pandemic productivity spurt.”

That would be bad, even taking into account the notorious volatility of productivity numbers, which frequently undergo substantial revision. Let’s set aside how productivity growth drives the long-term increase in living standards. A less-productive economy boosts the degree of difficulty for the Federal Reserve in managing a soft landing from the current inflation surge. This is one reason why the Biden administration described the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act, the CHIPs and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act as anti-inflationary. They supposedly would boost the productive capacity of the economy, dampening inflation.

The easy, Occam’s razor explanation here is one of mean reversion. Productivity growth is just returning to normal, or its longer-term baseline, after a temporary upshift. One reason GS doubts the explanatory power of that explanation: For the sectors best able to digitize, the impact of using these technologies has been ongoing. The bank points out that productivity “remains well above trend for the industries that were well-positioned to digitize the workplace, such as information technology (6.4% above trend) and professional services (5.1% above trend).”

So what are stronger explanations for the sharp reversal in the productivity data across the broad economy? Let’s have a look:

- Weird data. In a global economy that has (a) suffered its worst pandemic since the Great Influenza of 1918, (b) government shutdowns and restrictions, and (c) historic supply-chain snarls, economic stats are going to be funky for a while. This can be seen in the import and inventory numbers that form a key part of Gross Domestic Product — which then biases the “output” part of productivity stats. But another way of measuring output is through Gross Domestic Income. As a 2015 Council of Economic Advisers note explains, GDP “adds consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports,” while GDI adds “labor compensation, business profits, and other sources of income.” Typically the numbers are pretty close, but right now they aren’t, with GDI much stronger than GDP.GS: “While the official measure—output per worker in the nonfarm business sector—has risen at a paltry +0.8% annualized pace since 2019, both Gross Domestic Income per hour (+2.3%) and our monthly productivity proxy (+2.1%) suggest a pickup relative to the +1.5% long-term trend.” Indeed, economists will sometimes average the GDP and GDI numbers, and if you do that with the productivity data, it comes in right around that 1.5 percent long-term trend. Some comfort there, I guess.

- Panicky layoffs. The Goldman econ team cites research from economists Robert J. Gordon (Northwestern University) and Hassan Sayed (Princeton University) in their new NBER working paper, “A New Interpretation of Productivity Growth Dynamics in the Pre-Pandemic and Pandemic Era U.S. Economy, 1950-2022. This is a paper I’ve mentioned previously in this newsletter. The key insight from Gordon and Sayed is that much as happened during the GFC, panicked companies during the pandemic overreacted with “excess layoffs,” reducing headcount to unsustainably low levels. “Their subsequent unwind produced an illusory boom and bust in measured productivity,” GS explains.Interregnum: Why might productivity go up during a downturn? That is, why might the percent decline in aggregate hours worked be larger than the decline in output? One possible reason is a changing mix of workers with higher productivity workers keeping their jobs. Another: Retained workers up their game and work harder. With the rehiring comes a drop in productivity since businesses have actually not become wildly more efficient or innovative — except perhaps for the work-from-home phenomenon.

- Powell vs. productivity. After falling terribly behind the inflation curve during the pandemic, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and the central bank have been raising interest rates and resetting expectations. As they should. But one tradeoff here, as GS research finds, is that “monetary tightening depresses productivity growth in the short-run. … we estimate that the Fed-induced FCI tightening since last fall accounts for 0.8pp of the weakness in 2022 productivity growth. We expect this channel to continue to weigh on productivity growth in the second half of the year and possibly in 2023.” GS offers the possible explanation that firms expect the Fed-induced slowdown to be temporary and so are in no rush to slash payrolls given the cost and hassle of finding, hiring, and retraining new ones.

And the GS bottom line:

Taken together, we believe productivity growth slowed in 2022, but by much less than today’s GDP vintages indicate and to a level still above the pre-pandemic trend. Our estimates of the positive and negative factors net out to a +1.6% annualized pace since 2019, halfway between the pace of the official measure and the GDI-based crosscheck.

And again, that 1.6 percent number is just a tick above the long-term trend. Which isn’t nearly good enough for the American economy to grow as fast in the future as in the past, especially with a demographically-driven slowing in labor force growth. I sure hope what Washington has been doing lately helps boost productivity growth — because, you know, it obviously needs lots of help.

▶ China Aims for a Permanent Moon Base in the 2030s – Andrew Jones, IEEE Spectrum | Starting with robotic landing and orbiting missions in the 2020s, its designers envision a permanently inhabited lunar base by the mid-2030s. … These initial plans are vague, but senior figures in China’s space industry have noted huge, if challenging, possibilities that could greatly contribute to development on Earth. Ouyang Ziyuan, a cosmochemist and early driving force for Chinese lunar exploration, notes in a July talk the potential extraction of helium-3, delivered to the lunar surface by unfiltered solar wind, for nuclear fusion (which would require major breakthroughs on Earth and in space). Another possibility is 3D printing of solar panels at the moon’s equator, which would capture solar energy to be transmitted to Earth by lasers or microwaves. … As with NASA’s Artemis plan, Ouyang notes that the moon is a stepping-stone to other destinations in the solar system, both through learning and as a launchpad.

▶ Pace of Climate Change Sends Economists Back to Drawing Board – Lydia DePillis, The New York Times | To be sure, most economists still think there’s an important place for carbon pricing, and squirm when the White House pushes for lower gas prices. “We all cringe,” said James H. Stock, an economist who serves as vice provost for climate and sustainability at Harvard University. But all things considered, he said, a $7,500 tax credit and reliable charging network might be as powerful as high gas prices in getting someone to buy an electric vehicle. In that sense, subsidies are a variant of pricing policy: They effectively raise the cost of fossil fuels relative to renewable alternatives. Only recently did the supply of those alternatives reach the point where a tax credit would make the difference, on a large scale, between buying an electric vehicle or not.

▶ Advancing Nuclear Energy – The Breakthrough Institute | Advanced nuclear reactors can play a key role in cost-effective decarbonization of the national power sector, reliably supporting a high-renewables energy system. Updated, realistic cost assumptions and accurate operational characteristics reveal that advanced nuclear technologies provide high value for a clean electricity grid and possess significant market potential. Emerging advanced nuclear technologies will ultimately compete in the marketplace based on cost, operating parameters, and the ability to meet diverse customer needs, shifting the balance among which technologies become dominant.

▶ American workers need lots and lots of robots – Noah Smith, Noahpinion | Frankly, every time I’ve read about this “rise of the robots” fear, I’ve felt the urge to tear my hair out. Because there were always two huge, huge problems with the thesis. The first is that while it makes a great science fiction story, so far there just aren’t any signs that it’s happening. And the second problem is that if we really want to change our economy in all the ways we’ve been hoping — reshoring manufacturing from China, securing supply chains, preventing inflationary bottlenecks, and so on — we’re going to need quite a lot of automation. Indeed, if the progressive project is to be revived in America, it will need robots to carry it forward.

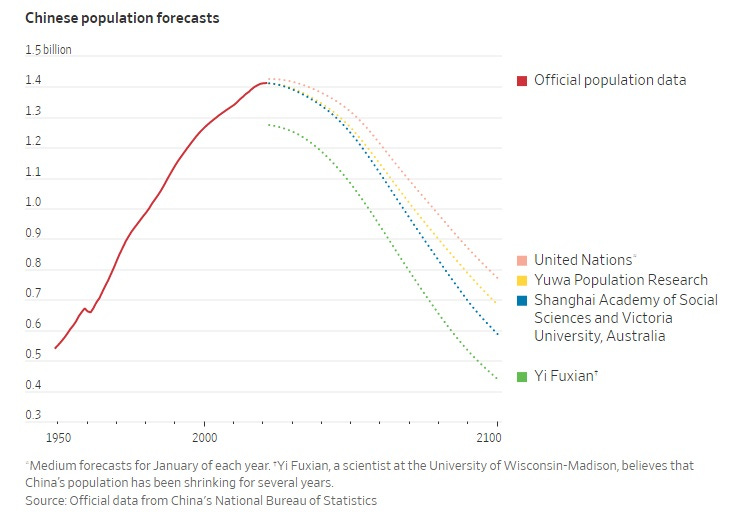

▶ China’s Economic Slump Bodes Ill for Birth Numbers – Liyan Qi, The Wall Street Journal | “The zero-Covid policy is like adding frost to snow, worsening a trend of declining births,” said Yi Fuxian, a scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who believes that China’s population has been shrinking for several years already. He estimates that China’s Covid-prevention measures, which he says contributed to a sharp drop in marriages in 2020 and 2021, will cause a reduction in births by about one million over the course of 2021 and 2022. Yuwa Population Research, a group of half a dozen Chinese demographers and economists, earlier this year also forecast a population decline starting in 2022. The group projected the Chinese population will shrink to 685 million by 2100. He Yafu, a demographer affiliated with the think tank, cited the economic slowdown and Covid controls as factors speeding up the drop. Beijing last month allowed single women to receive funds to cover some expenses during maternity leave.

▶ Germany to keep nuclear plants on standby in case of energy crunch – Guy Chazan, Financial Times | Germany said that two of its remaining three nuclear power stations, which were all due to close at the end of the year, would be kept on stand-by to provide back-up in the event of a winter energy crunch. Robert Habeck, economy minister, said the Isar II plant in Bavaria and the Neckarwestheim facility in Baden-Württemberg would form an “operational reserve” until April, as Germany grappled with the fallout from Russia’s decision to halt the flow of gas into the country. This would ensure “that over the winter they can make an additional contribution to the electricity network in southern Germany in 2022-23, in case it’s necessary”, he said. The government, a coalition of Social Democrats, Greens and the liberal Free Democrats, had in recent months come under huge pressure to rethink its opposition to nuclear energy as the scale of Germany’s energy crisis emerged.

I would love to have participated in this rather darkly hilarious effort, but that SCE cut our power all afternoon these last 3 days anyway – very helpful.

— Casey Handmer, PhD (@CJHandmer) September 5, 2022

Let us enumerate the ways this effort is bizarre. pic.twitter.com/inp2kohqaS

Sign up for the Ledger

Weekly analysis from AEI’s Economic Policy Studies scholars