UBI Needs AGI to Make Sense

August 09, 2024

The case for universal basic income is in large part aesthetic. The minimalist simplicity and elegance of UBI constitute a big part of its appeal: a single solution addressing a multitude of societal complexities. By providing all citizens an unconditional stipend, UBI tackles poverty, inequality, and economic instability — especially from technological flux — in one swooping, graceful motion. Its streamlined structure bypasses bureaucratic bottlenecks and tangles, while its inherent adaptability allows individuals to create their own life paths.

Just lovely. Public policy by way of Jony Ive. Imagine someone in Silicon Valley who worries about tech unemployment from human-level artificial general intelligence. Also imagine such a person stumbling upon UBI after a quick Google query and thinking, “Money for people. What an obvious solution. I must tell the world of this, especially those gloomy idiots in Washington.”

But here’s the thing: America already has a rather extensive welfare state, and it’s deeply embedded in our society.

So many programs: Social Security to provide retirement, disability, and survivor benefits. Medicare to offer health insurance for seniors and certain disabled individuals. Medicaid to supply health coverage for low-income populations. SNAP to furnish food assistance to low-income individuals and families. TANF to deliver cash aid and support services to needy families with children. SSI to grant cash assistance to low-income aged, blind, or disabled persons. Section 8 to facilitate affordable housing for low-income families. The Earned Income Tax Credit to extend tax credits to low- and moderate-income workers. The Child Tax Credit to afford financial support to families with children. Unemployment Insurance to dispense temporary aid to eligible jobless workers.

So, yeah, it’s a lot. But it also does a lot. (And my brilliant AEI colleague spend a lot of their time figuring out how to make it all work even better and get more bang for the buck.)

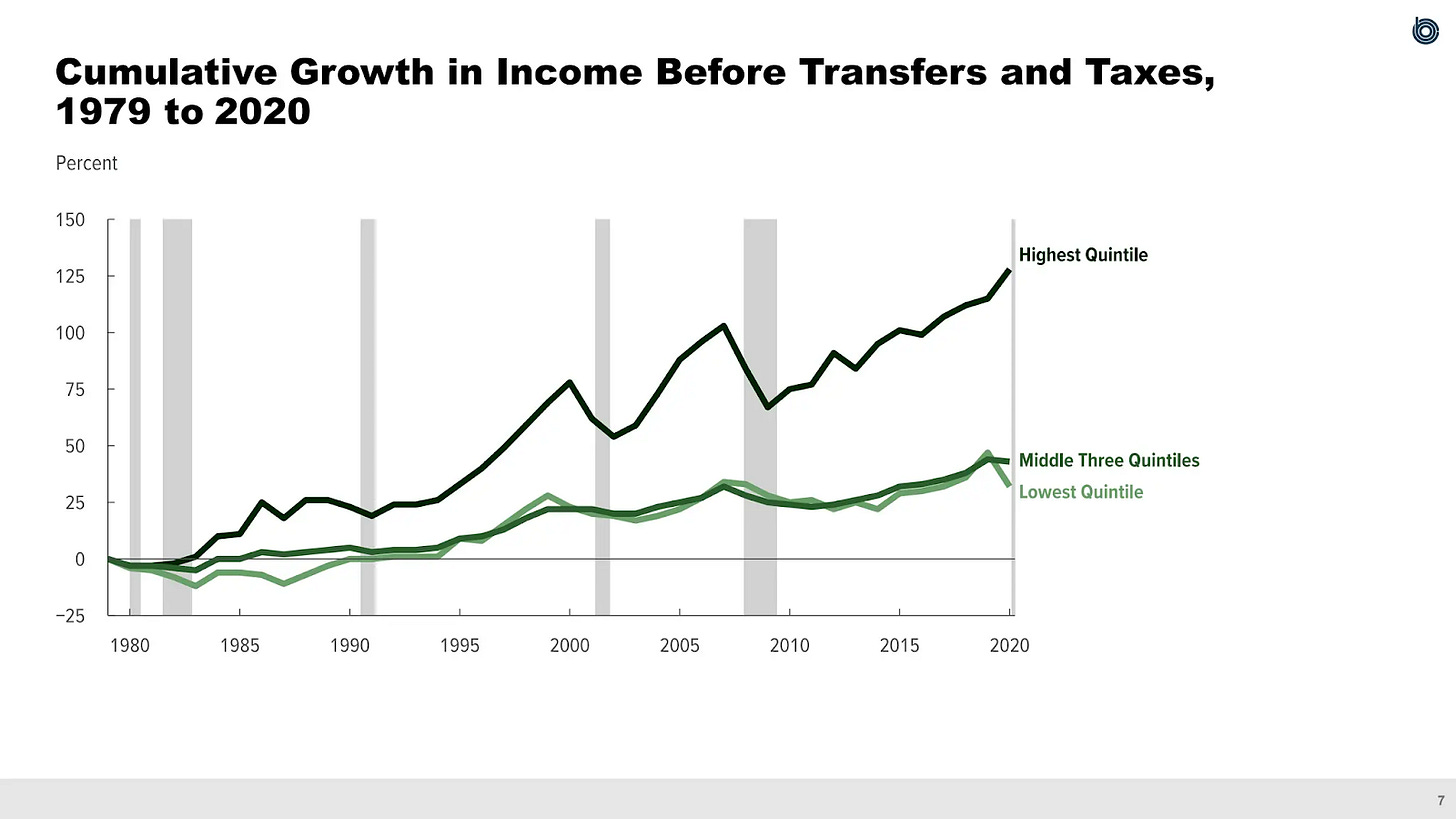

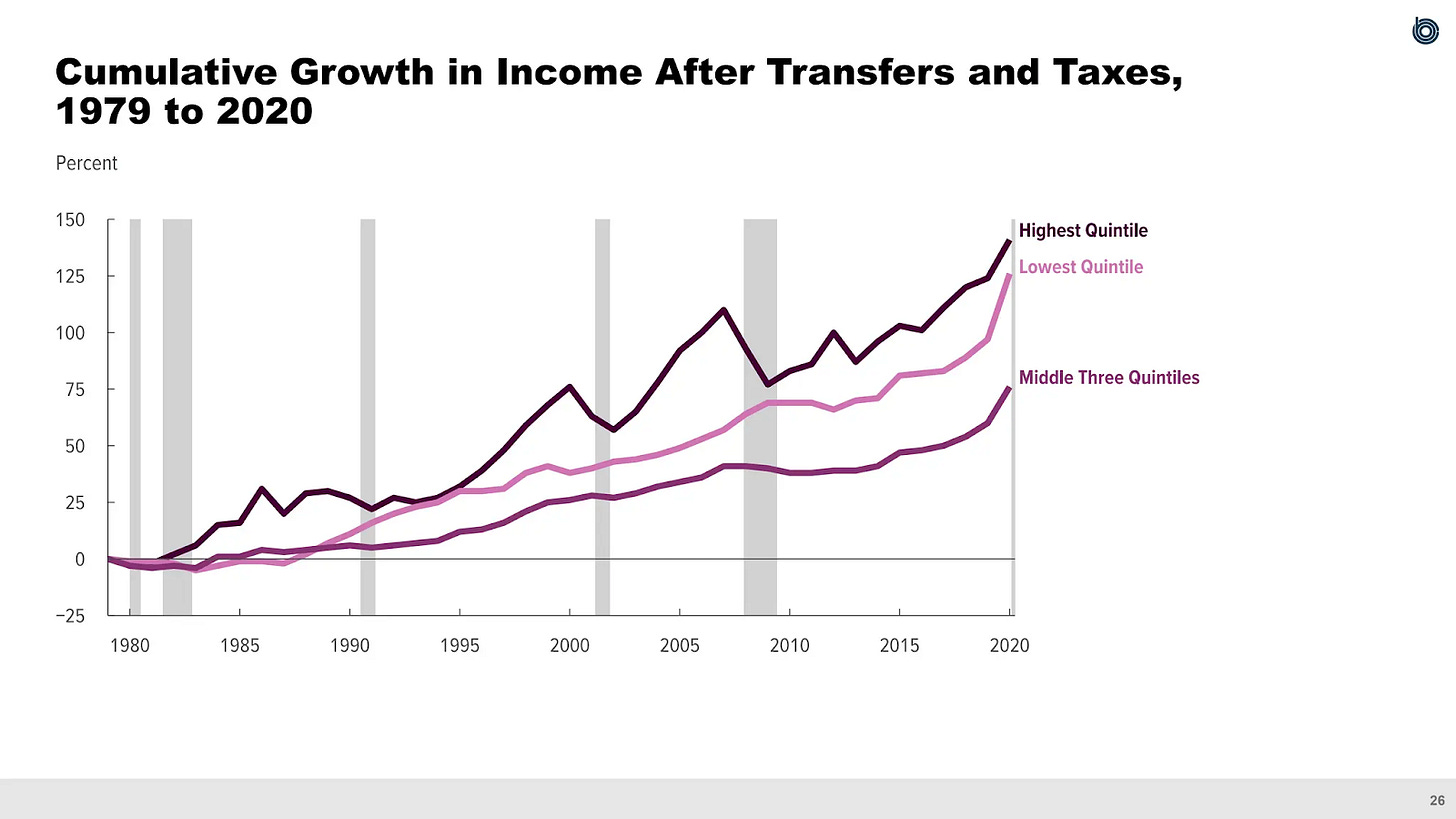

Consider: From 1979 through 2022, middle-class income (inflation-adjusted) rose by 43 percent, according to a Congressional Budget Office calculation that includes wage, business, and investment income, as well as payments from government programs that people pay into while working, such as Social Security and Medicare. That number jumps to 76 percent if you include means-tested transfers — Medicaid and children’s health insurance, SNAP, Supplemental Security Income, housing assistance — and refundable tax credits.

No doubt the idea of swapping our tangled welfare system for a simple and elegant UBI is appealing in theory. But as with totally changing the US tax code, there needs to be considerable and demonstrable upside to seriously consider such a heavy lift.

And I interpret the new research on UBI, supported by OpenAI’s Sam Altman, as failing to provide such compelling up-side evidence. The project tracked 1,000 low-income individuals given $1,000 monthly for three years. Compared to a control group, UBI recipients worked less, earned less, and enjoyed more leisure time. Their income fell by about $1,500 — not counting the UBI payments — annually due to reduced work hours and labor participation. For every $1 received, household income dropped by over 20 cents. (“This is a pretty substantial effect.” ) The extra time wasn’t used for job searching or entrepreneurship, but mainly for leisure activities. Younger participants were slightly more likely to pursue education. While the study found “precursors” to entrepreneurialism — “entrepreneurial orientation and intention” — it didn’t show significant increases in business creation or human capital investments. (“In short: the transfers largely financed consumption, with minimal savings and ~$0 impact on net worth. Financial health improved in years 1-2 but reverted by year 3.”)

Nor did physical health and mental health improve, really. (There was no effect of the transfer on physical health, measured via self-reports, clinical outcomes derived from blood draws, and admin records of mortality.” … “The cash generated big improvements in stress and mental health, but they were short-lived.”)

This from my AEI colleague Kevin Corinth:

The employment declines in these studies are important, despite the fact that they are based on short-term cash infusions that likely understate the effect of a permanent, nationwide policy. They suggest that a true Universal Basic Income (UBI), layered on top of existing benefits to low-income families, would reduce work effort. But they are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to employment concerns. In reality, a UBI of $12,000 for every adult in the United States would be impossibly expensive, costing over $3 trillion per year. It is hard to imagine Congress greenlighting a policy to increase federal spending by more than 50 percent—not to mention reigniting inflation—while already-high federal debt continues to climb.

As Corinth sees it, a more constructive approach to welfare reform would balance immediate support with long-term self-sufficiency. This involves offering temporary aid during hardships, expanding work requirements for able-bodied adults receiving long-term assistance, and reducing marriage penalties in the system.

And as for replacing the entire safety net with a UBI — setting aside political feasibility — the odds seem high that the simple and elegant system wouldn’t remain that way for long. My AEI colleague Michael Strain writes:

Another issue with UBI is its lack of realism. If UBI were introduced here, it wouldn’t take long for a politician to point out that, say, blind people need more support than those without physical disabilities. And then that workers who are disabled on the job deserve extra support over and above their base-line UBI benefit. And then it wouldn’t take very long for UBI to transform into something that looks very much like the system we have today. Why, then, change in the first place?

As I see it, the best case for a UBI remains a science-fictional one: a world where labor markets are completely upended by brilliant machines able to match or exceed humans in both cognitive and physical capabilities. So not a today thing, though certainly worth continuing to study and discuss.

While AGI’s timeline remains uncertain, let’s consider a scenario where AI significantly reduces workforce participation but there are still lots of jobs for humans. Rather than focusing solely on distributing AI-driven income, governments should prioritize making work as financially attractive as possible and helping people leverage AI to boost their productivity. This could involve substantial earnings subsidies, with many workers possibly receiving most of their income from government checks rather than employers. Such an approach, while not ideal, would be preferable to a world where these individuals contribute nothing and rely entirely on smart machine-generated wealth.

Sign up for the Ledger

Weekly analysis from AEI’s Economic Policy Studies scholars