(Un)Happy 50th Anniversary of the Great Stagnation! But There’s Hope!

January 02, 2023

The quarter century after World War II has been called a “golden age” for the American economy. Real GDP growth averaged nearly 4 percent annually, driven by labor productivity growth of nearly 3 percent. Then came a sudden and shocking slowdown in 1973. (So happy 50th anniversary!) And whatever you want to call the past half-century — the Great Stagnation, the Long Stagnation — the slower pace of productivity and economic growth has continued for so long that it really is a New Normal, or maybe just, you know, normal.

One way to gauge the importance of the downshift is through a simple thought experiment once offered by economist Jason Furman when he was the top economist in the Obama White House:

… what if productivity growth from 1973 to 2013 had continued at its pace from the previous 25 years? In this scenario, incomes would have been 58 percent higher in 2013. If these gains were distributed proportionately in 2013, the median household would have had an additional $30,000 in income. Had income inequality and labor force participation not worsened markedly, middle-class incomes would be nearly twice as high.

A few more numbers for context and then a discussion:

- 1973 saw the start of nasty recession extending from November of that year through March 1975, including five consecutive quarters of declining productivity, beginning a stretch where productivity growth averaged just 1.1 percent through 1981.

- Since then, real GDP growth has averaged 2.5 percent, including a further deceleration to 2 percent in the 2000s.

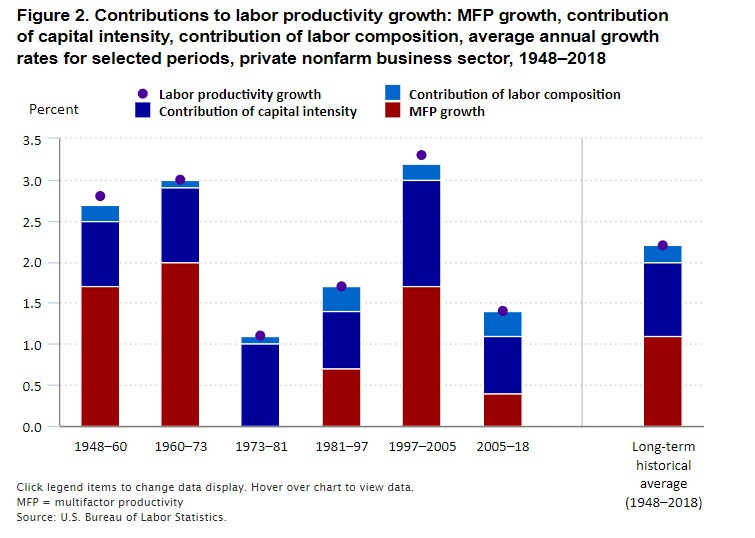

Likewise, labor productivity growth has mostly been underwhelming compared to its immediate postwar performance:

- Notice, particularly, what’s been happening with the slowdown total factor productivity, which is stands-in for technological progress and business practice innovation. It accounts for nearly half of long-term productivity growth, including most of growth during the postwar “golden age.” But pretty much weak-sauce since then, with the exception of the boomy mid-1990s to mid-2000s.

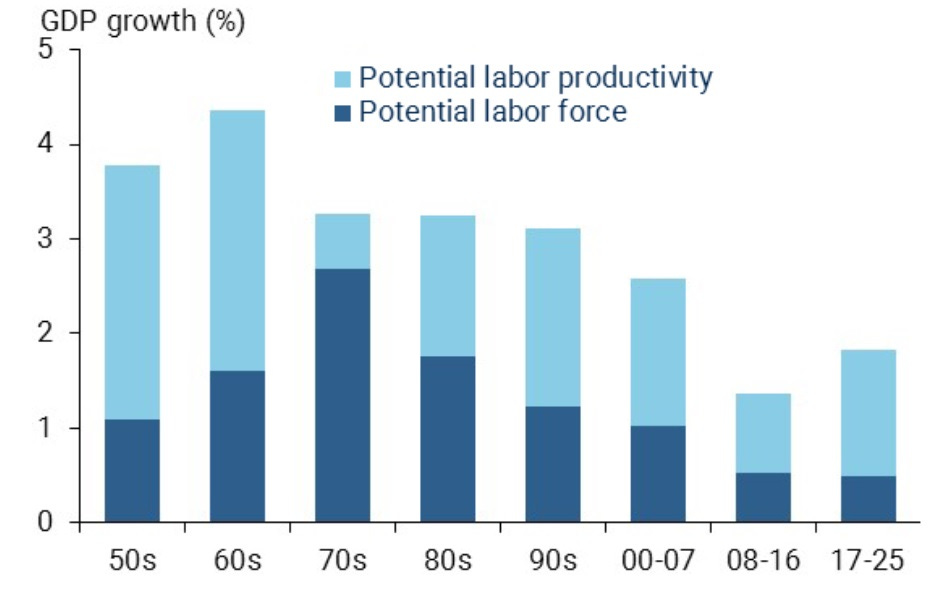

Finally, this is a great chart that shows just important faster productivity growth is to future economic growth given the slowdown in labor-force growth due to baby boomer retirements and falling fertility rates:

So what happened? Where do I start?

Among the possible culprits: the early 1970s oil shock, full exploitation of the great inventions of the second phase of the Industrial Revolution, the Information and Communications Technology Revolution being important but not (yet) as important as the second IR, the “low-hanging” fruit of innovation all having been mostly picked, too much anti-growth regulation, too little venturesome R&D, too little economic dynamism, too much societal risk aversion.

In a 2013 analysis, the Congressional Budget Office concluded, “Researchers still have not reached consensus on a comprehensive explanation for the slowdown.” And not much has changed in the nearly decade since. In the 2022 book of economic history, Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century, University of California, Berkeley, economist Brad DeLong concludes the slowdown “remains a mystery even today.” If this mystery were an orange, there would be much juice left to squeeze.

How might the Great Coronavirus Pandemic change things? An initial surge in the second half of 2020 and first half of 2021 — along with a bit stronger productivity growth leading into the outbreak — raised hopes that another productivity boom was emerging. This apparent revival, noted economists, Robert J. Gordon and Hassan Sayed in a paper last summer, was interpreted by some as “caused by automation, artificial intelligence, and a massive investment by households in the equipment and software needed to conduct work from home.” But Gordon and Sayed suggest a different explanation: the surge was entirely due to higher productivity at businesses whose employees could work remotely. When you smooth the ups and downs of the business cycle, the economists conclude, “there appears to be a consistent growth rate of 1.4 percent (2005-19) roughly equal to 1.5 percent (1973-95), leaving the dot.com achievement of 3.3 percent as a historic outlier as it recedes further into the past.”

In other words, the Great Stagnation or Permanent New Normal continues. This newsletter, however, is devoted to the notion that acceleration is possible through public policy that supports scientists, technologists, and entrepreneurs. As such, I am always on high alert for signs of pro-progress actions and attitudes, as well as achievements. The recent nuclear fusion breakthrough qualifies as one. So does the pro-nuclear stance of the Biden administration. Outside of policy, I would point to the AppleTV+ streaming series For All Mankind — the Space Race never ends, and it’s kind of awesome — about which I’ve written several times.

Along those lines, I wanted to highlight the recent paper “Economic impacts of AI-augmented R&D” by Tamay Besiroglu (MIT FutureTech), Nicholas Emery-Xu (UCLA, MIT FutureTech), and Neil Thompson (MIT FutureTech).

Interregnum. FutureTech is “an interdisciplinary group that studies the foundations of progress in computing: what are the most important trends, how do they underpin economic prosperity, and how can we harness them to sustain and promote productivity growth.” And both Besiroglu and Thompson have been featured previously in Faster, Please!)

The paper look at one of my favorite themes: the potential impact of the deployment of AI-deep learning techniques on scientific progress and economic growth by making researchers more productive. From the paper:

Since its emergence around 2010, deep learning has rapidly become the most important technique in Artificial Intelligence (AI), producing an array of scientific firsts in areas as diverse as protein folding, drug discovery, integrated chip design, and weather prediction. As more scientists and engineers adopt deep learning, it is important to consider what effect widespread deployment would have on scientific progress and, ultimately, economic growth. … We find that deep learning’s idea production function depends notably more on capital. This greater dependence implies that more capital will be deployed per scientist in AI-augmented R&D, boosting scientists’ productivity and economy more broadly. Specifically our point estimates, when analysed in the context of a standard semi-endogenous growth model of the US economy, suggest that AI-augmented areas of R&D would increase the rate of productivity growth by between 1.7- and 2-fold compared to the historical average rate observed over the past 70 years.

That sort of increase in US productivity growth would be pretty significant and by itself would enable the US economy to grow as fast in the future as in the past. Again, from the paper:

With the widespread adoption of deep learning raising ideas production in the economy to this level of capital intensity, we would expect the productivity growth rate to rise to between 2.1% and 2.4%. To put that in context, this would amount to increase of between 1.7- and 2-fold relative to the 1.2% average U.S. productivity growth from 1948 to 2021, and a 2.6- to 3-fold increase against the post-2000 0.8% growth (Fed 2022). Thus, our results indicate that if adopting deep learning in other areas of R&D allows those areas to leverage capital better in the same way that computer vision has, it will represent a substantial acceleration of scientific progress.

Look, I could have used this essay to focus on Sunday’s 60 Minutes segment — “Scientists say planet in midst of sixth mass extinction, Earth’s wildlife running out of places to live” — pushing the notion that there are too many people who want to live too well. (Was Paul “Population Bomb” Ehrlich interviewed? Of course, he was. My favorite sound bite of his: “Too many people, too much consumption and growth mania.” Same as it ever was.) And maybe I still will. But I would prefer spending my time on finding and presenting realistic reasons to be optimistic about the kind of future we can have with better decision-making and a better attitude — and a bit of luck.

Micro Reads

▶ Still Wrong! New Year’s Paul Ehrlich Interview on CBS’s 60 Minutes – Marian L. Tupy, Human Progress | I realize that CBS has no time or space for the authors of Superabundance – a book showing that resources are getting more, rather than less, abundant. But why not interview Nobel Prize-winning economists like Paul Romer, Angus Deaton, and Michael Kremer, who never bought into the overpopulation nonsense? And if that’s a stretch, why not interview smart Democrats, like Lawrence H. Summers (Bill Clinton’s Secretary of the Treasury) or Jason Furman (Barack Obama’s Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers)? They, too, argue that we do not have an “overpopulation problem.” Or was 60 Minutes only looking for scholars willing to confirm the pre-determined narrative of doom and gloom?

▶ Let Joe Manchin have his pipeline – Matthew Yglesias, Slow Boring | To achieve a 100 percent clean electricity grid, we are going to need technological breakthroughs in batteries, in advanced geothermal, in advanced nuclear, and ideally in more than one of those. There are permitting barriers to interregional clean energy transmission, creating utility-scale wind and solar, geothermal exploration, and getting NRC approvals for new reactor designs. Some cities are moving to ban gas hookups in new construction, which is good for the environment. Even better for the environment would be to get the jurisdictions that are adopting clean building codes to massively upzone so that lots of affordable new green buildings get built. We need policy work on freight rail electrification. We need technical work on aviation and maritime shipping.

▶ Net Zero Isn’t Possible Without Nuclear – Editors, Bloomberg | To bring global emissions goals within reach, nuclear output will need to roughly double by 2050, according to the International Energy Agency. Unfortunately, the world is moving backward in key respects. Nuclear’s share of global energy production declined to 10.1% in 2020, from 17.5% in 1996. In the US, about a dozen reactors have shut since 2013 and more are on the chopping block. According to the Energy Information Administration, nuclear’s share of US generation will fall from about 19% today to 11% by 2050, even as electricity demand rises. Although renewables will pick up some of the slack, fossil fuels are expected to predominate for decades.

▶ Wage Inequality May Be Starting to Reverse – Greg Ip, The Wall Street Journal | Inflation inflicted misery on pretty much all workers in 2022. Yet peek below the surface, and the year’s most consequential economic development may be what happened between different groups of workers. In the decades before the pandemic, the wages of lower-paid, less skilled hourly employees steadily lost ground to those of skilled workers, college graduates, managers and professionals. In the two years since, those trends have sharply reversed.

▶ Teen’s leukemia goes into remission after experimental gene-editing therapy – Jennifer Couzin-Frankel, Science | A 13-year-old girl, the first patient to be treated with a new kind of cancer therapy aimed at inducing remission, is doing well more than 6 months later, researchers reported at a conference last week. The teen, who has leukemia (acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells shown), joined a clinical trial of an experimental immune therapy using genetically modified, donor-provided T cells, the sentries of the immune system. Researchers edited single bases of DNA inside these cells to help them better target the girl’s cancer, then infused them. Her cancer went into remission and, as a result, she was able to undergo a stem cell transplant that doctors hope will brighten her prognosis.

▶ The start-ups seeking a cure for old age – Hannah Kuchler, Financial Times | Finding the key to prolonging life would benefit us all, but money to fund the search is hard to come by. Healthcare investors typically want to see short-term returns — unlikely, in metformin’s case, since its patent has long expired. Governments, meanwhile, prioritise research into diseases. Into this gap have stepped tech billionaires including Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, Israeli entrepreneur Yuri Milner, and through Alphabet, Google co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, who are funding new models that aim to combine the best of business and academia without the pressure for short-term returns. … The billions being made available to longevity researchers could be a gift to a humanity too distracted by today’s problems to fund a long-term revolution in healthcare. Their interest could be a “win-win”: billionaires tempted by the idea of living ever longer fund a longevity field that would not thrive without them.

Sign up for the Ledger

Weekly analysis from AEI’s Economic Policy Studies scholars