Why MIT Was Smart to Again Require SAT and ACT Scores

March 31, 2022

By James Pethokoukis

In This Issue

- 5QQ: 5 Quick Questions for … Naomi Schaefer Riley on SAT and ACT college tests, and MIT’s reversal

- The Essay: China’s top-down innovation policy is failing. America and the West shouldn’t try to mimic it.

- Macro Reads: STEM immigration, self-driving cars, the crypto caucus in Congress, and more …

- Nano Reads

Quote of the Issue

“If we have a world in which China is harnessing the meritocratic idea to reinforce the power of the Communist Party, and America at the same time is dismantling meritocracy or softening meritocracy … if you have these two things going on at the same time, America loses. China becomes a massive version of Singapore. America becomes, I don’t know, a version of Brazil or something like that, and you lose. They win.” – Adrian Wooldridge, author of The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World

5QQ

❓❓❓❓❓ 5 Quick Questions for … Naomi Schaefer Riley on SAT and ACT college tests, and MIT’s reversal

Item: “Students applying to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2022 will have to submit SAT or ACT exam scores, the university announced on Monday, nearly two years after suspending the requirement because the pandemic had disrupted testing for many applicants. The requirement was reinstated ‘in order to help us continue to build a diverse and talented M.I.T.,’ Stu Schmill, the dean of admissions and student financial services and a 1986 graduate, said in a statement. ‘Our research shows standardized tests help us better assess the academic preparedness of all applicants,” he said. The decision will affect first-year students or transfer students who want to enroll at M.I.T. in 2023.’” (The New York Times, March 28, 2022)

Naomi Schaefer Riley is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and the author of six books. Her work appears in outlets such as The New York Times, TheWall Street Journal, and TheWashington Post. In a recent Bloomberg Opinion article, “Dropping the SATs Opens the Door to More Legacy Students,” she and James Piereson argued that eliminating standardized testing requirements for admission into elite universities could give legacy applicants further advantages.

1/ You argue that dropping SATs will give greater weight to less objective measures like personal essays, allowing elite schools to admit more legacies. What incentive do they face to prefer legacies to high-SAT earners?

The decision is not exactly a binary one. The question is whether it is worth it to schools to give a little on the SAT scores in order to gain a little more goodwill with alumni. Elite schools want it to be known among their alumni population that they reward loyalty, that their children will be welcomed as members of the university “family.” They have made the calculation that this kind of family continuity is worth it for their bottom line.

2/ Why don’t advocates of dropping the SATs instead advocate for giving other factors more weight? What do they think is to be gained from getting rid of them altogether?

I think they’ve already tried giving other factors more weight and it hasn’t solved the problem they wanted to solve — which is, how do we get more kids of certain preferred races into our institutions? For years, college admissions officers have studied essays and teacher recommendations and GPAs looking for ways to justify admitting students who wouldn’t otherwise get in. Particularly for public institutions where the data on admissions is going to be public, it is much easier to just eliminate the evidence of how far you are willing to lower standards in order to get your ideal racial mix.

3/ If it meant keeping standardized testing requirements for college admissions, would you favor providing test prep resources to high school students from disadvantaged families? Why or why not?

Of course, we could offer test prep resources to disadvantaged families. Khan Academy already offers it for free. But I don’t think it would be tough to find a private donor who would provide in-person tutors, frankly. (I would rather put Kaplan in charge of such instruction than give poorly performing public schools the money to train their own teachers.) But I think what such an experiment would ultimately show is the limits of test prep for fixing this problem. Even the most elite tutoring services for test prep will acknowledge that they are never going to raise a child’s score by more than 100 points. Test prep may take a kid whose test scores qualify him for Haverford and put him closer to Harvard but it is not going to take a kid who is qualified for SUNY Binghamton and get him into Harvard.

4/ You have argued that “admitting students with lower SAT scores to fulfill diversity quotas may prevent those students from achieving their academic and career goals — something they might have done at a lower-tier school.” How might eliminating SAT requirements harm such students?

Because the SATs are a good predictor of a student’s first-year grades, ignoring them can mean that on average a school admits more kids who cannot handle the work at a particular school and it means lower graduation rates overall. When the University of California eliminated affirmative action, there were fewer black and Hispanic kids admitted to the top schools like Berkeley, but the graduation rates of black and Hispanic students in the system as a whole improved dramatically. It is useful to note two things about this. First, a college degree from just about any school is worth more than a year of college at an elite school. Second, especially in STEM fields like engineering, there is not much difference in the salaries several years out of kids who attended elite schools and kids who attended schools at lower tiers. By admitting kids to schools whose work they can’t handle, we are denying them a chance for graduation and a comparable salary to the one they would have achieved.

5/ MIT recently announced that it will begin requiring SAT/ACT test scores for applicants after suspending the requirement during the pandemic. Are other elite schools likely to follow suit?

Some elite schools may follow suit but it is noteworthy that MIT was the first domino to fall because it is a STEM school. Other universities have easier ways of admitting less qualified students and still getting them to graduate — they funnel them into humanities majors, where the courses are typically less demanding and the grades can be more easily inflated. According to researchers at the University of Texas at Austin, “More than a third of black (40%) and Latino (37%) [STEM] students switch majors before earning a degree, compared with 29% of white STEM students.” So unless MIT is going to start graduating a lot more humanities and social science majors, the school is going to have to ensure that the students it admits are qualified to graduate in STEM fields.

The Essay

📉 China’s top-down innovation policy is failing. America and the West shouldn’t try to mimic it.

Item: “Last year, President Xi Jinping seemed all but invincible. Now, his push to steer China away from capitalism and the West has thrown the Chinese economy into uncertainty and exposed faint cracks in his hold on power. Chinese policy makers became alarmed at the end of last year by how sharply growth had slowed after Mr. Xi tightened controls on private businesses, from tech giants to property developers. … [Some] voices in the party have recently suggested a measure of skepticism over whether now is the right time to pursue Mr. Xi’s vision of remaking China in the spirit of Mao Zedong.” (The Wall Street Journal, March 15, 2022)

The (possibly) two most powerful pieces of propaganda for the idea that the 21st Century will be the Chinese Century have nothing do with international sporting events or global consumer technology companies. One of them is the country’s many architecturally stunning airport terminals that gobsmack foreign visitors (especially American journalists more familiar with some rather pedestrian American airport counterparts).

The other bit of pro-China propaganda was not meant as pro-China propaganda. But intentional or not, I think it functioned as such. In 2010, the Washington, DC-based, anti-debt group Citizens Against Government Waste aired this ad at a time of considerable controversy over rising federal deficit spending in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis:

The Washington Post called the “The Chinese Professor” ad “the latest and most inflammatory of a series of China-related advertisements appearing across the United States. … More than a spasm of political season piling-on, the ads underscore a broader shift in American society toward a more fearful view of China. Inspired by China’s rise and a perceived fall in the standing of the United States, the ads have historical parallels to the American reaction to Japan in the 1980s and to the Soviet threat.” The ad may not have led to a balanced federal budget, but it was kind of demoralizing.

The GDP stats are always greener on the other side of the Pacific

It also didn’t help American confidence that the GFC called into question the stability of the American free enterprise system versus the more state-managed Chinese version of capitalism. Among the major world economies, only China, India, and Indonesia did not contract during the crisis. Indeed, if I had to add a third nominee for Most Effective Piece of Propaganda, it would be Chinese economic growth statistics over the past decades. Year after year of annual gains of close to 10 percent. Impressive numbers with the added benefits of (mostly) being true.

Those strong growth stats even turned into a Donald Trump talking point. As he said during a 2016 presidential debate with Hillary Clinton: “China is growing at 7 percent. And that for them is a catastrophically low number. We are growing — our last report came out — and it’s right around the 1 percent level. And I think it’s going down. … Look, our country is stagnant.”

But to speak about today’s Chinese economy in such glowing terms would be a mistake. Doing so would be the economic version of how many Western experts overestimated the capabilities of Russia’s military. (Or indeed, the Soviet Russian economy during the Cold War.) This may yet become the Chinese Century, but that long march toward global superpower dominance seems to have stalled. As my AEI colleague Derek Scissors said recently, “The era of rapid growth is ending.”

Another slowdown by an Asian economy? Nothing to see here.

Well, of course it is, right? China was a very poor country with a small economy that has undergone decades of catch-up growth thanks to urbanization and liberalization. Slower economic growth is a natural part of any developing nation’s economic evolution as it grows richer and the opportunities for easy catch-up gains dissipate. The big things China could do to boost its productive capacity have largely already been done. You can only open to foreign trade and investment or move a worker from field to factory once.

Other Asian economies have gone through two or three decades of hyper-growth, then a downshift. South Korea notched plenty of years of double-digit growth in the 1970s, 1980, and 1990s. Today it has a per capita GDP the same as Italy and was growing at 3 percent annually before the Great Pandemic. A similar China slowdown? No news here, right?

Or is there? Scissors argues that China is slowing more quickly than it should. And that’s due primarily to its own economic policy choices. “It would take shocking policy shifts to avoid near-stagnation,” he concludes in a late 2021 paper, “China’s growth spurt ends. What’s next?”

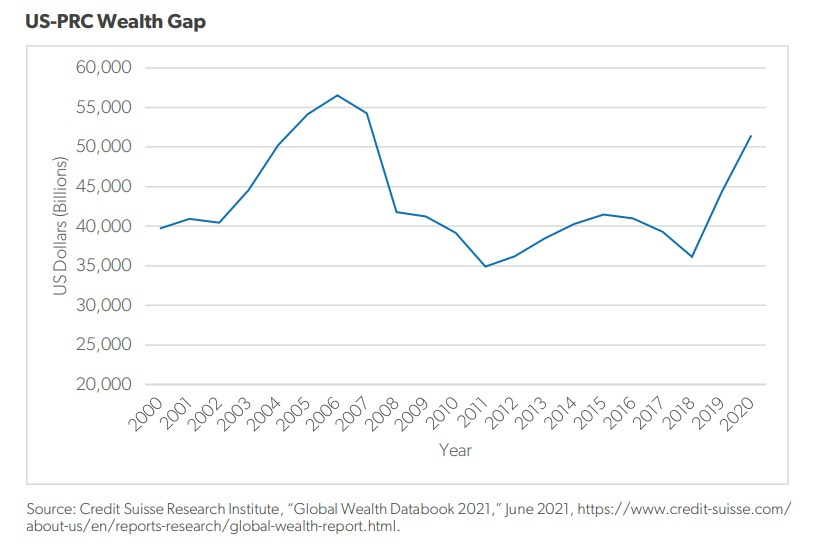

First, let’s look at the broad economic slowdown. Rather than GDP, Scissors thinks estimates of total national wealth — the thing that buys everything from “needed national imports and new weapons to personal shelter and clothing” — often give a better sense of an economy’s international position. [The figures below come originally from Credit Suisse’s annual global wealth report which defines wealth as the “value of financial assets plus real assets (principally housing) owned by households, minus their debts.”]

And while China’s wealth continues to rise, it’s not as fast as America’s. Scissors: “From 2000 to 2010, it soared nearly 600 percent. From 2010 to 2020, it rose less than 200 percent. Natural slowing? From 2010 to 2020, the wealth advantage of the US over the PRC climbed from $39 trillion to $51 trillion.”

China’s self-defeating retreat from economic liberalization

One possible conclusion to be drawn from that growing gap is that China has started doing something wrong. Perhaps it suggests that generating leading-edge technological invention and business innovation “requires a vibrant, freely competing private sector the CCP renounced years ago,” Scissors writes. “For example, the anti-monopoly law is used to threaten private actors, while state enterprises gain dominant shares through orchestrated mergers. In what is represented as a boom year, the 500 largest private companies accounted for 1.5 percent of total employment. They have not and will not be allowed to drive growth.”

The reality of China’s retreat from economic liberalization can be clearly seen in President Xi Jinping’s “common prosperity” program, actions meant to accelerate China’s shift away from Western-style market capitalism and economic openness. “Mr. Xi last year rallied the whole government behind his campaign to clamp down on capitalist forces, from tightening Beijing’s grip over data accumulated by the private sector to restricting overseas share listings and shutting off lending to property firms, in a realignment with socialist principles,” The Wall Street Journal reports.

An increased emphasis on more top-down control of the economy is a bet that the state can effectively encourage innovation through government investment spending in promising sectors. Easier said (and spent) than done. For example: China has spent billions of dollars in recent years trying to catch up to the world’s most advanced semiconductor makers, but state-supported firms have never commercially produced an advanced semiconductor, the WSJ adds.

The productivity principle

If China hasn’t figured out another way to innovate — a way different than the West does — that such a failure can’t be underestimated in its long-term importance to Chinese economic power and thus geopolitical heft. China must boost the productive capacity and power of its economy. While productivity growth is crucial for just about any economy, including America’s, this is especially the case for China.

Two reasons: First, it’s an economy with a population set to shrink and age rapidly over the coming decades even as its working-age population has been shrinking since the middle of the last decade. Second, public investment — long a key driver of growth — is reaching a point of sharply diminishing returns where it has become less and less effective in that role. As analysts Roland Rajah and Alyssa Leng wrote last month in the report “Revising Down the Rise of China” for Australia’s Lowy Institute: “Public capital per worker in China is now much higher than that seen in most other emerging economies when they were at a similar level of economic development — including the East Asian miracle economies in the past — and already comparable to some advanced economies.”

This leaves higher worker productivity as the key to fast economic growth going forward. But Chinese productivity growth has been slowing or even turned negative.

Indeed, even China’s pre-downshift productivity performance looks less than miraculous once its low starting point is taken into account. As Rajah and Leng note: “When China began its reform and opening up period in the late 1970s, its output per worker was just 2 percent of that in America, compared to around 10–25 percent when each of the East Asian miracle economies generally began their own periods of super-fast growth. At comparable levels of development, Chinese productivity growth appears to have underperformed by a wide margin.”

Looking ahead, the analysts think there are good reasons, in addition to those raised by AEI’s Scissors, to believe that productivity growth will continue to weaken “even assuming Chinese policy proves reasonably successful.”

The reform requirements for sustaining rapid growth get harder to successfully deliver as countries develop, at both a technical and political level. … Abolishing China’s hukou system, for example, is a longstanding and well-recognised growth priority that would likely deliver substantial economic (and social) benefits — supporting the manufacturing sector, reducing precautionary saving, encouraging stronger household consumption, and enabling a smoother adjustment in the housing market. Nonetheless, hukou reform continues to proceed slowly.

Previous East Asian miracle economies benefited substantially from relatively unfettered access to Western markets and technologies. But geopolitics means China can no longer do so and instead faces the prospect of intensifying “decoupling” with the United States and potentially other advanced Western economies. … [Such] technological restrictions will reduce China’s access to the global technological frontier while also disrupting its own technological innovation by reducing the scope for cross-border collaboration.

The impact of China’s big downshift

If they’re right that Chinese productivity growth going forward is slower than the consensus forecast, then economic growth will be slower, as well. Here’s what that means: If China continues to grow at the expected 4 percent or 5 percent rate, it would make China the world’s undisputed economic and technological superpower by mid-century. Maybe the leading military, too. Welcome to the Chinese Century.

But: If China only grows around 2 percent to 3 percent a year, then the country’s future looks very different. From the Lowy report: “China would still likely become the world’s largest economy. But it would never establish a meaningful lead over the United States and would remain far less prosperous and productive per person than America, even by mid-century.”

Bottom line: China hasn’t proven there’s a way to become a high-productivity country that broadly pushes forward the tech frontier that doesn’t look a lot like Western-style market capitalism. But I’m concerned that some American policymakers are too impressed with China’s rapid economic rise and think Chinese “capitalism” with American characteristics has much merit. That perception has at least some role in Washington’s renewed interest in industrial policy where government favors certain industries as strategic sectors, such as chipmaking and AI.

Yes, I think government shouldn’t be afraid to encourage — such as through innovation prizes — certain clearly defined “moonshot” projects across disciplines. But the most important thing government can do is create a pro-entrepreneurial ecology through policy actions such as dramatically expanded science research investment, increased immigration, and pro-build regulation. In other words, the American Way of innovation. Because right now we’re finding out the Chinese Way doesn’t even work for China.

Micro Reads

🌐 STEM Immigration Is Critical to American National Security – Jeremy Neufeld, Institute for Progress | National security has often been a catalyst and cover for Washington doing hard things that needed to be done. And if geopolitical threats provide the political will to get serious about immigration, so be it. That said, there is a legitimate linkage between national security and immigration, as Neufeld explains: “America’s ability to attract the world’s leading minds has long been an asymmetric advantage.” And the Pentagon seems to agree when a recent report noted that “the most important asset our defense industrial base possesses isn’t machines or facilities, but people… Greater attention must be paid to workforce concerns… to maintain and develop the intellectual capital necessary to create and sustain war-winning weapon systems for the modern battlefield.” Lots of great charts in this piece, too. Here’s one:

🤖 Artificial intelligence beats eight world champions at bridge – Laura Spinny, The Guardian | I know, another day, another AI victory at a game you might play on a rainy day when the power is down and your phone is dead. But this win for the machines is worth highlighting. As Linney writes: The victory represents a new milestone for AI because in bridge players work with incomplete information and must react to the behaviour of several other players – a scenario far closer to human decision-making. In contrast, chess and Go – in both of which AIs have already beaten human champions – a player has a single opponent at a time and both are in possession of all the information. The AI program from French startup NukkAI calls its technology a big step forward in AI “explainability” because it explains its decisions as it goes along — a necessity in bridge, unlike Go or Chess. Impressive. Of course, there is evidence that the combo of human and AI is even more impressive, at least with Go.

🚘 Taking our next step in the City by the Bay – Waymo blog | With all the excitement of advances in biology, space, and energy, it’s easy to forget what a key role the prospect of self-driving cars has played in this latest cycle of tech enthusiasm. Yes, Elon Musk was wrong when he predicted in 2019 that Tesla would have a million robotaxis on roads in 2020. (He also offered this caveat: “Sometimes I am not on time, but I get it done.”) But progress in autonomous driving continues to happen. From Team Waymo yesterday:

This morning in San Francisco, a fully autonomous all-electric Jaguar I-PACE, with no human driver behind the wheel, picked up a Waymo engineer to get their morning coffee and go to work. Since sharing that we were ready to take the next step and begin testing fully autonomous operations in the city, we’ve begun fully autonomous rides with our San Francisco employees. They now join the thousands of Waymo One riders we’ve been serving in Arizona, making fully autonomous driving technology part of their daily lives.

💲 Meet the ‘crypto caucus’: the US lawmakers defending digital coins – Kiran Stacey, Financial Times | One of the recurring themes of Faster, Please! is the search for consensus and collaboration on the left and right for technological progress. So I found it both intriguing and inspirational that a small group of Democrats and Republicans joined forces to kill a sloppily written clause in the recently passed 2700-page infrastructure bill. As the FT explains, the rule would have forced brokers of cryptocurrency to report their transactions and customer information to the tax authorities.

Here’s the trouble: “The term ‘broker’ was so widely defined it could also apply to the software developers who make crypto products.” This rule could have really chilled the fast-growing industry. And who came to the rescue? “The row was a seminal moment for an eclectic group of crypto champions in Congress, made up of free-market libertarians, pro-business advocates, and leftwing technology utopians. This ‘crypto caucus’ is set to become one of the most powerful blocs on Capitol Hill in the coming years, as politicians rush to set the rules for one of the fastest-growing industries in the world.”

Nano Reads

▶ Vaccination Rates and COVID Outcomes across U.S. States – Robert J. Barro, NBER |

▶ Big cities’ brightest days lay ahead of them – Margaret O’Mara, New York Daily News |

▶ John Deere Tractors Plow Day and Night With No One in the Cab: Autonomous Farming Debuts in 2022 – Andy Corbley, Good News Network |

▶ Human-Algorithm Interactions: Evidence from Zillow.com – Runshan Fu, Ginger Zhe Jin & Meng Liu, NBER |

▶ Science and innovation policy in a new age of insecurity – Richard Jones, Soft Machines |

▶ Computerization of White Collar Jobs – Marcus Dillender & Eliza Forsythe, NBER |

▶ A hole in the ground could be the future of fusion power – James Temple, MIT Tech Review |

▶ Why BARDA Deserves More Funding – Nikki Teran, Institute for Progress |

▶ The lure of technocracy -Jason Crawford, Roots of Progress |

▶ Fusion without Fissiles: Superbombs and Wilderness Orion – ToughSF |

1/Some exciting things ahead for geothermal in the FY23 White House budget request. After a disappointingly flat budget in FY22, this is a major step forward that will mean big things for the geothermal industry, so a quick overview THREAD.

— Tim Latimer (@TimMLatimer) March 30, 2022

Sign up for the Ledger

Weekly analysis from AEI’s Economic Policy Studies scholars